An anthology of art & ideas

—Issue 4 out October 2021

Eds. Rachel Withers and Nicholas J. Jones

Issue 3:

The hills are alive

—exploring sound and environment

September 2021

Introduced by Rachel Withers

Somewhere in the literature on the history of ‘disembodied voices’ and recorded sound it’s mentioned that an early rationale for the invention of sound recording was its capacity to preserve for posterity ‘the voices of great men’. This issue of PRAKSIS Presents focuses on sound, the environment, field recording and the idea of the ‘soundscape’, a concept we owe to the founder of acoustic ecology studies, R Murray Schafer. Sadly, Schafer died this year on 14th August, at the very time Nicholas and I started to edit this issue. Celebrations of Schafer’s life, ideas and works now abound online, and alongside them we find the recorded voice of Schafer himself. It is poignant to hear him speak to us now that he has gone – in particular, to hear his reflections on the precious transience and uniqueness of ‘real’ sounds (as in, unrecorded sounds: live rather than recorded speech, for example). From what I’ve heard and read, I imagine Schafer would have shrugged off the designation ‘great man’, but there is also something resonant in the thought that when we listen to his voice now, one of sound recording’s earliest motivations – to keep alive important past utterances, voiced by their original speakers, at least as an echo for future generations – is being fulfilled.

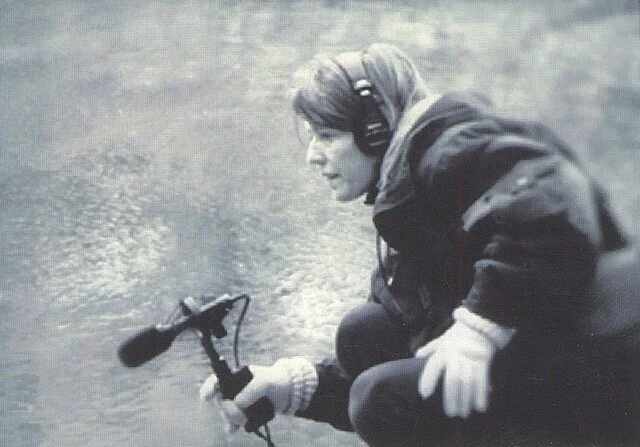

Many of Schafer’s core ideas are carried forward in this issue’s contents. Composer, sound ecologist and former colleague of Schafer’s Hildegard Westerkamp has made available to us Raven Dialogue, a seventeen-minute field recording of the winter soundscape of Saltspring Island, approximately 40 kilometres south-west of Vancouver, and she accompanies this with a short contextualising text. The recording initially seems sparse and austere but (in Schafer’s words) by ‘using our senses properly’ and listening with full engagement, we find ourselves immersed in an acoustic environment that is both saturated with subtle detail and spatially expansive: ‘mapped’ by a 360-degree long-distance ‘conversation’ between ravens in which the hiatuses seem as significant as the birds’ cries. ‘The existing soundscape is made of energy,’ Westerkamp notes, in her talk in this issue. ‘When we listen with intention, we meet that energy with our own,’ and we start to make discoveries. In Raven Dialogue, for example, we find that sound can have a temperature. With its continuous, complex crackle of melting ice and an occasional crunch of snow underfoot, this is the very sound of icy cold. ‘When you listen carefully to the soundscape, it becomes quite miraculous,’ said Schafer, but he also pointed out it is a practice that takes work and reflection. All of the works in this issue are born from processes of sustained and intensely close perception. They offer a great basis for deep listening and, we also hope, for ‘understanding yourself as a listener better,’ to borrow Westerkamp’s phrase.

Schafer observed that real, individual sounds are absolutely unique and unrepeatable. In the past, before the invention of sound recording, ‘every sound committed suicide, you might say, and would never be heard again – not exactly the same way’. The contributions we’ve included by composer and sound artist Annea Lockwood and sound artist and founder of the Gruenrecorder label Lasse-Marc Riek both chime with this idea. ‘Experience doing field recording clearly shows you that sound is unpredictable and can’t be controlled. The accidents that arise demonstrate the infinite number of variables in play’ notes Riek, while Lockwood underlines the centrality of sound’s unpredictability to her own practice as a composer, performer and field recordist. ‘If I like a particular mix of sounds at a certain spot on a river, I need to record it right away; tomorrow, that water riffle will be different, or might have vanished altogether,’ she observes.

Those who record the planet’s soundscapes do so with a deep concern not just for the uniqueness of original sounds, but for the creatures and conditions that create them: they too are under threat of disappearance and this knowledge is central to many of this issue’s discussions. The four recordings by Riek included here are extracted from Helgoland, a larger work sound-mapping the Heligoland archipelago – a wild and biodiverse environment that, thanks both to sheer chance and some recent human interventions, has survived earlier attempts at its annihilation. Riek characterises the work as a literal and metaphorical study in ecological resurgence – of the drive to survive. We experience this drive powerfully, indeed viscerally, when we listen to his recording of guillemots diving from the Heligoland cliffs into the sea. Yes, this is a recording, but when we give ourselves fully to the sound it becomes an electrifying, almost shredding, aural encounter with raw life.

Annea Lockwood’s Wild Energy also immerses the listener in the sounds of powerful elemental forces, but what we hear in the extract she’s provided introduces us to a different order of listening: something we might describe, borrowing a phrase from Walter Benjamin, as the aural unconscious. Benjamin’s ‘optical unconscious’ identified the new, paradoxical realm of unseeable things rendered visible to the human eye by photographic technology. Wild Energy is built (at least in part) from sounds that shape our world but that are inaudible except via technological intervention: for instance, the splitting of trees’ internal water columns at a time of drought, or pressure waves travelling under the surface of the sun, or the ultrasonic cries of bats and the vocalisations of Sei whales. Wild Energy can be experienced fully in a rural outdoor location at the Caramoor Center in New York State, and it was created to be heard within that wider soundscape; it is about connection. Lockwood’s purpose is not to amaze her listener with other-worldly sublimities but to cement our sense of our ‘visceral connection to earth’s forces’. She does this by introducing us to a soundscape that is both extraordinary and a constant underlying, unconscious component of our earthly lives.

Tze Yeung Ho’s essay is importantly a manifesto plea for biodiversity at the level of speech and song. In it, the composer explores the classical music world’s fixation on a mythical ideal of ‘pure’ performance: the reproduction in sung performances of ‘authentic,’ ‘perfectly accented’ articulations of different languages. ‘Accents are an essential part of us as human beings’, he points out. Rather than fetishizing an impossible ideal of perfection, he asks, why not re-focus on the affective and musical qualities of performance and celebrate the constantly-evolving ‘heard identities’ of individual performers? For Ho, individual, local and regional vocal identities are not an obstacle to be eliminated but a rich resource for a composer to be explored and inspired by. In his essay, he shares the approaches and tactics that he uses to put this ethos into practice.

This issue’s theme arose from PRAKSIS’s Residency 17, Climata: Capturing Change at a Time of Ecological Crisis. The scheduled start of this residency in Spring 2020 coincided with the outbreak of Covid-19, but its participants responded resourcefully to the changed formats that lockdown compelled. Working collectively and communicating online, they produced two radio broadcasts that documented their acoustic explorations of the places in which they were sheltering, and thus these two programmes present a montage of intimate “lockdown soundscapes” from three different continents. Alongside the Climata broadcasts are a series of talks that were further rich components of the residency’s programme of learning, discussion and development.

Seamus Harahan wields his video camera in a way that bears many comparisons with the acoustic field recording tactics of our other contributors. He videos the ‘found activity’ that he encounters while roaming in (usually) urban locations, and this forms the starting points for his finished works. In Crow Jane, Harahan’s camera homes in on a crow that has taken fervent possession of a straggly scrap of unidentifiable, presumably edible, stuff. He studies the bird as it defends its prize against all other avian comers. In the process, the scrap disintegrates and the crow’s treasure becomes smaller and smaller; at one point, the bird tries to gather all the fragments up in its beak, but fails. Crow Jane’s soundtrack, a grimly melancholy song by Skip James in which the narrator laments shooting down the woman he loves, forms a pregnant parallel to the bird’s behaviour and signals to us that it is human perversity, not bird logic, that is under Harahan’s magnifying glass. It’s tempting to scale this parable up to global scale and think about the ways that human beings’ extractive activities are dissipating the basic resources we need to stay alive and destroying both landscapes and soundscapes. “You know I never missed my water till my well went dry…” We say thanks to Seamus for letting us use this work as a kind of ironic coda to The hills are alive – and to all our contributors, for their generous and active collaboration in the realisation of this issue of PRAKSIS Presents.

Helgoland

Lasse-Marc Riek

Crow Jane [for Nora Joung]

Seamus Harahan

Working with (not against) heard identities in music

Tze Yeung Ho

Wild Energy

Annea Lockwood

Raven Dialogue

Hildegard Westerkamp

Tuning in, Sounding out

Talks and radio sessions from residency 17, Climata

Issue 2:

Heavy burdens, Happy burdens

—probing complexities of making art work that bears witness to processes of history

Summer 2021

Introduced by Rachel Withers

The sky is blue, the path is dusty and dry, and the artist is striding along with his wooden staff in hand and his easel slung on his back. Seeking the warmth of the morning sun on his face, he has swept off his hat as he goes. It is swinging in his other hand as he nears his two acquaintances, who’ve been waiting for him at the bend in the road. They make a considerable show of doffing their hats in greeting. “Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet,” says the younger-looking of the two, who is conspicuously smarter and more self-possessed than his companion. “You have every indication of excellent weather for your day’s work.”

Gustave Courbet’s reply is unrecorded and indeed totally hypothetical, since the encounter represented in his famous 1853 painting The Meeting is a “real allegory” and a complex fiction. (It is also a “speechless” one, in the sense that all its personnel are shown with their mouths shut; maybe it’s this that tempts one to add one’s own dialogue). It is a work that makes various powerful truth claims through its reflexive use of allegory: for example, by positioning the artist himself within the picture’s frame, as a witness, a truth-teller and the bearer of a historical as well as a literal burden. Back in the 1960s art historian Linda Nochlin established that Courbet’s self-portrait in The Meeting reiterates nearly millennium-old iconography: he painted himself as the mythical figure of the Wandering Jew. Having sinned in some way against the living Christ, the Wandering Jew was doomed to roam the earth until the Second Coming: he is the embodiment of endless witnessing, a kind of “walking proof”. The Wandering Jew’s identity and narrative have been reinvented and reinvested ad infinitum, and for the radicals of the nineteenth century he symbolised the oppressed manual labourer, a kind of worker that Courbet manifestly was not. That complicates but does not necessarily undermine the manifesto call for freedom, independence and dignity in labour painted by Courbet into The Meeting. The man greeting the artist is his patron Alfred Bruyas, the affluent bougeois who commissioned the picture in which he appears. Courbet shoulders his backpack with conspicuous ease and responds to Bruyas, in beard-language, that the old patron-client relationship no longer applies.

Jane Blocker concludes her 2009 book Seeing Witness: Visuality and the Ethics of Testimony with the proposition that under certain circumstances, “contemporary art can productively throw into question the claims that are made on the real and at the same time maintain an ethical responsibility to reality” (p. 128); it can also help us to see, appreciate and interrogate the subject or the apparatus that sees. Courbet’s paradoxical realist allegory shows that older practices have achieved this too, and its interweaving of ancient imagery with the figure of the artist as witness and the bearer of a burden of responsibility makes it, I think, a pregnant companion and introduction to the diverse works we’ve brought together in this issue of PRAKSIS Presents.

Heavy burdens, Happy burdens probes the complexities, responsibilities and possibilities of making art works that bear witness to processes of history or memory. All the featured works use historical materials, mythological imagery or traditional narrative to address present-day issues that are both personal and global in their importance. In the process, tricky questions relating to reality, truth, identity, subjectivity and seriousness are thrown up. Each work has its own particular reflexive relationship to its historical subject, and in different ways they all ask their audience to reflect on this. In some works, the artist’s affective labour is a conscious point of focus: bearing witness can be heavy but it can also be joyful, sometimes at one and the same time. In others, distancing strategies are explored: for example, by hypothesising the potential of decentering the anthropocentric view within the representation of ecological crisis. And while reflecting on this labour and these approaches, viewers are prompted to think about their own responsibilities as fellow bearers of the burdens of history and memory.

A statement by PRAKSIS 2019 resident Syowia Kyambi was key in helping us crystallise this issue’s theme. “We carry our histories on our backs, hunched over and barely heard, constantly swimming against the stream… The body holds, codes and re-codes, sharing a multitude of layered stories… Collective history weaves a web in the memory of our contemporary bodies.” In her video essay Becoming Kaspale, the artist reflects on the emergence of Kaspale, a multifaceted, creolised avatar or performance medium through which Kyambi revisits and processes the trauma of living through Kenyan dictator Daniel arap Moi’s regime. Kaspale is a “joker”, but a very serious one; their mission is the symbolic demolition of Nyayo House, a physical embodiment of, and metaphor for, Moi’s nationalist-authoritarian ideology. As we listen to the artist’s voice, we watch her on screen; ochre, silver and gold help prepare her body for the transformation. It’s been exciting working with Kyambi on the resolution of Becoming Kaspale, and we thank her – and indeed all our contributors – for their active participation in the PRAKSIS Presents editorial process.

Sayed Sattar Hasan’s Portrett av Hasansen also focuses on self-reinvention as a means of interrogating notions of personal and collective heritage, and the spirit of the joker is also alive in his work. Portrett av Hasansen marries a photographic portrait of Hasan with an iconic 1896 image of the Norwegian explorer and polymath Fridtjov Nansen. This gives birth to “Hasansen”, a charismatic masquerader who seems to partake of the unorthodoxy and daring of both his (male) parents. Hei, Herr Hasansen! Like Courbet, the figure of Hasansen announces a certain disregard for proprieties and hierarchies, but when we look at this work it is not possible to forget the wider historic and social legacies, preconceptions and prejudices against which Hasan pitches his photographic-performative gambit.

Nina Torp’s Methods of Pattern Making [Lepenski Vir] is a work in progress – a drafted first chapter of a video project that will probe the intellectual and ideological frameworks within which some of the world’s oldest archaeological remains were rediscovered and that continue to shape their contemporary display. As in an archaeological dig, Methods of Pattern Making is stratigraphic. It overlays and filters visual documentation of ancient remains with patterns and forms that meld modern rationalist schemata and modernist aesthetics. However, the goals of Torp’s personal stratigraphy are poetic and critical rather than rationalistic, and designed to activate the viewer’s own questions about the present-day interests and needs that inform contemporary presentations of the deep past.

Juan Covelli’s El Salto is also a first instalment of a larger project that he hopes to complete in 2023. It focuses on El Salto, a famous “natural spectacle” to the south-west of Bogotá, and reflects the artist’s concerns with digital colonialism and its impacts on people and the environment, alongside his practices of detailed research into the histories of representation. This multilayered work posits “landscape” not simply as an artistic genre but as a technology of colonial domination, and its response to this is to propose a delegation of the “burden” of representation to non-human agencies. By opening ourselves up to the point of view of machines (algorithms, drones) and subordinating the idea of human agency, it asks, might our species discover better ways of deploying the powerful technologies we have developed, and learning to live within rather than to “master” the global ecology we are presently destroying?

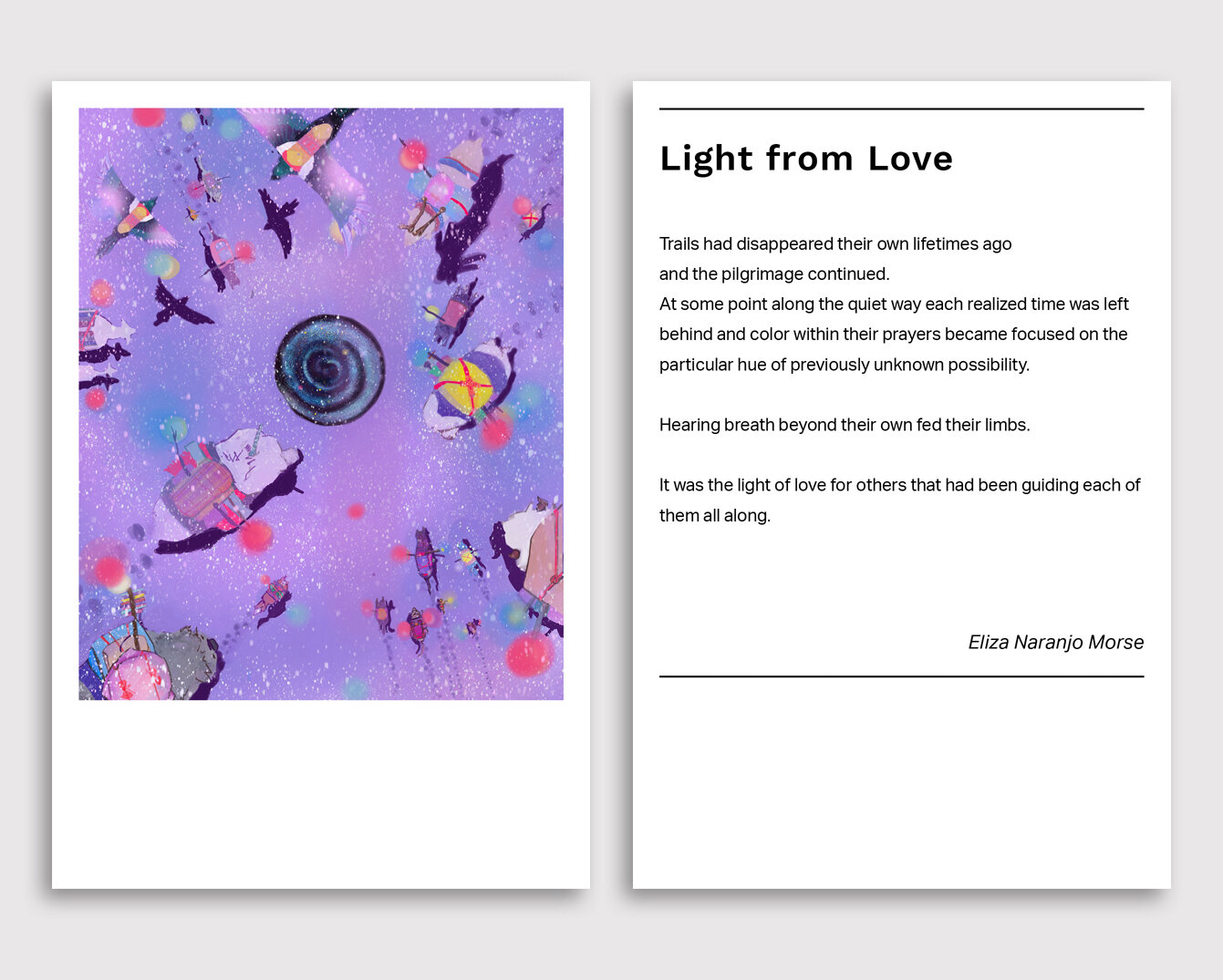

Eliza Naranjo Morse’s Light from Love is a gesture of giving. It consists of a downloadable PDF that can be printed as an unlimited multiple work: a small card bearing an image and a poem, that can be gifted without limit. Optimistic and full of compassion, it shows a collective of animals, each carrying a small cargo or backpack, against a background that reminds us of the wider cosmos we all inhabit. Naranjo Morse sees this work as representative of a worldview that she has been fortunate to inherit from her elders, and hopes that it will evoke reflection and consideration of how the choices we make affect others, now and in the future. We might read Light from Love as a token of the kind of selfhood - one that accepts its instabilities, dependencies and vulnerabilities, and that learns to carry its hard inheritances, if not joyfully, then willingly - that many now advocate as the only solution to contemporary society’s problems.

El Salto

Juan Covelli

Portrett av Hasansen

Sayed Sattar Hasan

Becoming Kaspale

Syowia Kyambi

Light from Love

Eliza Naranjo Morse

Issue 1:

I give to you & you give to me

June 2021

—looking at processes of giving and exchange in the arts

Introduced by Rachel Withers

During the PRAKSIS team’s early planning meetings, a conversation arose as to whether the “Presents” in “PRAKSIS Presents” is acting as a verb (“PRAKSIS is pleased to present…) or a noun (“here, in this part of our website, are presents from PRAKSIS”). It’s doing both, of course. PRAKSIS Presents is an anthology of diverse, interesting and stimulating presents for the eye and mind, presented month by month during the organisation’s fifth birthday year and planned to continue beyond it: a way of sharing PRAKSIS’s ongoing activities, conversations, projects and exchanges, as well as highlighting items from its increasingly well-stocked archive, to as wide a public as possible.

To underline the double meaning, we have tied up this first instalment with a big bow, sparkly paper and a gift tag saying “I give to you and you give to me”. This is the opening line of True Love, a Bing Crosby and Grace Kelly duet from the 1956 musical High Society, and so PRAKSIS Presents’s very first gift to you is an earworm, and maybe a rather undesirable one at that. (For the recor, it’s said that the only way to get rid of one earworm is to trade it in for another. My recommendation would be Stevie Wonder’s “Yester-Me, Yester-You, Yesterday”, overheard, yes, yesterday at the supermarket. That will potentially stay with you for days.) Maudlin and hollow-sounding, True Love would be an ideal candidate for redeployment in a Scorsese-style film edit: extreme violence on screen, Bing and Grace simultaneously schmaltzing away over the Dolby stereo speaker system.

Sorry for the unpleasant image, but that’s the way present-giving goes. Gifts are complicated things whose very definition is up for grabs, and the nature and value of gifting systems are (and have long been) open to debate. The exchanging of gifts may constitute the most basic expression of the human social contract; it can be a way of saying “I recognise your humanity; let’s work together”. It can be a means to gain practical and symbolic leverage, as in the famous truism about the non-existent “free lunch”: to give a gift is to create an obligation and to receive one is to become indebted. Gift-giving can be a threat or sneak attack (as in the offer you can’t refuse, or those pesky ancient Greeks bearing gifts) but it can also be an act of wild, reckless extravagance, an acte gratuit and an end in itself. Gifting systems can be an assertion of a specific kind of cultural identity and status, or a gesture of resistance in the face of other economies (neoliberal capitalism, most obviously). The gift can also be a medium, a platform for creative expression. Within capitalism, artists are persistently implicitly or explicitly characterised as spontaneous, selfless, unstoppable givers of social gifts. The triangular relationship between gift economics, market economics and the practice of making art keeps recurring as both a problem and a field of possibility in theories and discussions of contemporary art and culture.

Within this issue, 2017 PRAKSIS resident Famous New Media Artist Jeremy Bailey introduces YOUar, an experiment in the creation, curating and marketing of Augmented Reality art that speaks directly to the complexities mapped out above. YOUar is an online gallery that shows and distributes AR sculptures – a fun way, as Bailey explains, to collect significant three-dimensional pieces without the housekeeping hassles presented by great big lumps of physical stuff. However, there are twists in Bailey’s business model. For example, all YOUar’s sculptures feature the artist as well as their work. In his own piece Brass and Wood Semicircles (2020), Bailey appears in his hallmark awful white polo and sawn-off jeans, cheerfully (and ridiculously) hefting the monumental work of the title, Atlas-style, into the air.

There is no need to beware these artists bearing sculptures, though, because YOUar’s go-getting marketing rhetoric is a little deceptive. In this gallery, 100% of each work’s selling price goes back to its creator, and most of the artists represented are female and/or of colour: in other words, not part of the big-bucks artworld’s continuing dominant demographic. So, for both Bailey and YOUar’s collectors, the trading of artwork evidently has a good deal to do with the assertion of a social contract that rejects standard capitalist economics and ensures that artists’ social gifts should not be acquired on the cheap. Bailey reports that many customers choose to pay more than the asking price for the works they collect. Arguably, among the key gifts being traded via YOUar’s at times laugh-out-loud virtual sculptures are the senses of resistance and solidarity, and a positive rejection of the capitalist “art of the deal”. For PRAKSIS Presents, Bailey has worked with Chicagoan artist and feminist Shawné Michaelain Holloway to produce a special edition of her work “emphasis on the Y (or the first time I gave my girlfriend head was in Indiana).obj” (2021), in what he describes as “a lesbian-forward colour palette of delicate lavender”. Within this issue’s pages you will find Shawné and her Robert-Indiana-inspired work, and can saucily twirl them both through a full three hundred and sixty degrees before you buy. We challenge you to resist investing!

In her trenchant and detailed essay Access to Tools, U.S. West Coast artist and musician Nina Sarnelle sets out some historical, economic and ideological contexts for understanding The Whole Sell, a barter-based e-store which she co-created following her involvement with the 2020 PRAKSIS residency Live or Buy. By browsing each work listed in The Whole Sell, viewers will discover the barter “price” its creator has set for it. Works can be swapped for uploads of specific photos or video footage, donation to chosen campaigns, or other tasks (“touching a Tesla”, the creepy task – or dare – set by artist Chester Vincent Toye, being one of the most peculiar).

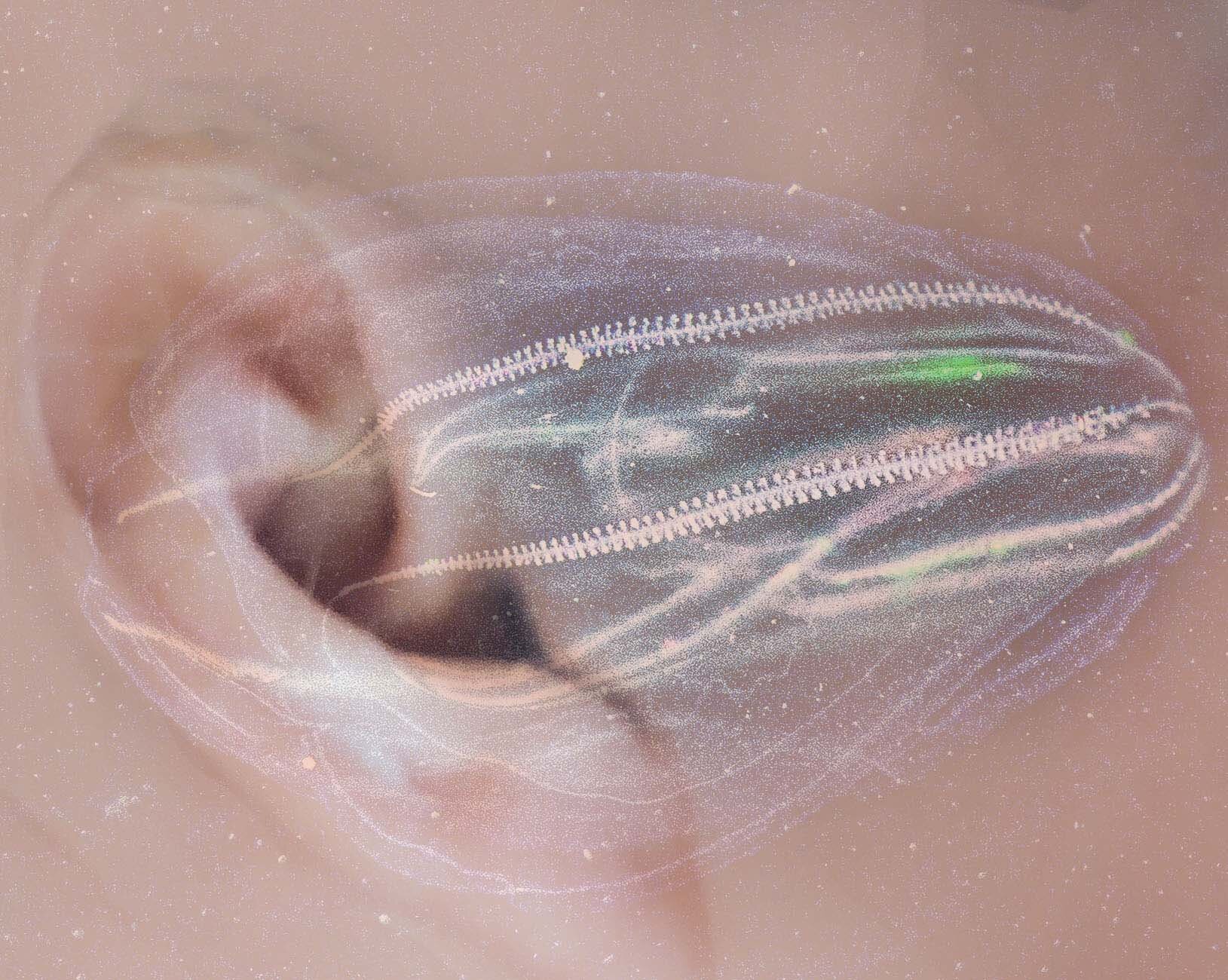

Sarnelle locates the inspiration for the project in Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog (1968-71), and specifically in its ideological problems. Her essay indicts the Catalog’s galloping individualism and white, male ethnocentrism and traces the evolution of these tendencies into high-tech neoliberalism. “The WEC,” she writes, “peddled a quasi-libertarian ethos based on a naive blend of DIY meritocracy and tech optimism: the same ethos that inspired the founding fathers of Silicon Valley.” The ideological “tools” of Brand’s Catalog, she points out, have in the long term brought us globally distributed “surveillance, mass data collection and algorithmic oppression”; commodification and gamified lives, heightened alienation and a deep social polarisation fostered by digital and social media. Sarnelle goes on to discuss the significance of The Whole Sell’s substitution of a visualisation of a black hole for the “Blue Marble” view of the earth featured on Brand’s Catalog cover. An anti-triumphalist, “terrifying image” pointing up the fragility of human existence in a basically indifferent universe, the “donut” of the black hole is designed to counter the narcissistic geocentrism of the earlier publication’s imagery.

The Whole Sell, Sarnelle explains, attempts to think through the complexities of critical cultural production in conditions where art production seems deeply implicated in capitalist patterns of exploitative labour, and where there is clearly no “outside” from which to launch a critique. Drawing on the ideas of (amongst others) Andrea Fraser and Audre Lord, she frames The Whole Sell as a way of posing immanent critical questions (“What is cultural capital? How and why do artists sell ideas? What’s the difference between interaction and transaction?”) and proposing “modest”, “tentative” and “ephemeral” alternatives to business as usual. “Each piece [on the site],” she suggests, “becomes a small gift to be “repaid” in reciprocal acts, initiating a reflection on what we each value in art, culture and relationships… The Whole Sell has been engineered as a kind of tool, providing an alternative framework for art distribution, valuation, exchange and interaction.”

The interrelation of gifting, gift economics and art making forms one important facet of this issue’s theme. Equally important are the practices of creative hybridisation, cross-fertilisation and “infection”, in positive (and also maybe not so positive) senses. Since the start of 2020, responsible people around the world have been striving not to give to each other: muffling our faces, washing our hands, coughing into our elbows and avoiding one another entirely in an effort not to pass on a potentially deadly disease. The soundtrack for this would be “I’ll try my best not to give to you, and thank you for not giving to me”. Nevertheless, at PRAKSIS as elsewhere in the art world, the drive to give and receive imaginative gifts, to infect others’ imaginations, to feed one’s own work and ideas through a collective process, would simply not be stopped, and throughout 2020 up to the present it has continued and flourished online.

The residents of Climata: Capturing Change at a Time of Ecological Crisis, scheduled to run in Oslo in the spring and autumn of 2020, were particularly hard-hit and particularly resilient in their response. Meeting digitally to pursue questions of sound and ecological change, the group recorded and shared the aural environments in which they were immersed during the unexpected condition of a pandemic lockdown. One upshot of the residents’ interactions is Climata: a hub for sound and ecology, launching imminently and to appear soon in this issue. The project is intended as a global repository for field recordings that reflect and investigate changes in the world’s aural environment: reflections of a time of crisis, but also potentially motivations for change and inspirations for practical kinds of remedial action. While unwanted sound constitutes noise, wanted sounds might be thought of in a Cagean sense as sharing the condition of music, and the possibilities that digital technology offers to share the ephemeral phenomenon of sound across time and continents seems deeply poetically – and also politically – resonant. The hub’s content will be freely available online and contributions responding to its various sub-sections are actively sought; please consider getting involved.

The politics and poetics of collaboration were also of crucial concern to the participants of PRAKSIS Residency 7, For a Rainy Day: Publishing as a Site of Collectivisation in autumn of 2017. Slowly evolving section by section following this residency was the print publication Don’t Rest, Narrate, produced by Oslo’s Torpedo Press and designers Eller med a and launched via an online event in Spring 2021. Partly a collectively designed artists’ book and partly a reader, Don’t Rest, Narrate contains sections looking at radical publishing and the art of the book, the politics of collaboration, copyright and copyleft, and more besides. One of this project’s priorities was to try, through the strategic, collectively-conceived combinations of image and text that punctuate the book, to embody the affects of a shared creative process, with its tensions, misunderstandings and miscommunications, surprises, hilarity and joyful epiphanies. This issue of PRAKSIS Presents includes links to a video generated collectively by the residency group, plus the recording of the book’s launch discussion. Copies of the book are available and purchasable via PRAKSIS’s website.

This issue also features a conversation between Nicole Rafiki, creator of the Norwegian cultural project RAI (Rafiki Arts Initiatives), and PRAKSIS director Nicholas John Jones. RAI was founded to provide a platform and meeting space for Black Norwegian creatives, and it is presently at work developing art-therapeutic community projects for the Oslo area and working with OCA (Office for Contemporary Art Norway) to showcase work by artists whose approach is, in Rafiki’s words, “transnational and complex”. RAI’s agendas are inflected by ideas of fluidity and liminality — identity and culture understood as multi-centred, mutable and heterogenous. In her interview, Rafiki reflects on her early experience growing up in a largely white Norwegian monoculture: a key influence in her project to create environments “where race is not a defining factor.” Jones and Rafiki will be in frequent dialogue as she expands and develops RAI’s projects and networks - a trading of ideas that will undoubtedly be of great mutual benefit to both organizations.

Last but not least in this issue’s collection is A Tapeworm without a gut (sketches for disaster protofiction), a digital project combining still and moving image and text by artist and writer Gary Zhexi Zhang, a participant in PRAKSIS’s first (spring 2016) residency, New Technology and the Post-Human. Zhang’s Tapeworm takes this issue’s theme of exchange in a different, maybe disquieting direction. His interest is in the fascinating dynamics of parasitism, a situation where an invading organism helps itself, unbidden, to the hospitality of a host body but in the process (needing to keep its host alive) effectively and paradoxically becomes a kind of host itself. One of Zhang’s inspirations was the parasite louse Cymothoa exigua, which, he writes, “takes the place of the tongue of a fish — squats firm on the tongue of the host — shuffles in between the cheeks, and makes itself at home... The bug sucks, supplants, and inhabits, introducing itself to the mouth in place of the native tongue which it has secretly drained of blood. The fish is left largely unharmed, somewhat augmented. The louse is a homemaker; the uninvited guest becomes the unexpected host.” Parasitism is undeniably a kind of giving and receiving – but a very, very posthuman kind, devoid of any hint of the operation of a social contract. “The parasitical invitation refuses exchange value, rejecting the commensuration of a transactional ethics,” Zhang observes. In the course of this introduction I have travelled from earworms to tapeworms, and maybe I’ve now gone far enough; sorry, again, for starting this text with one unsavoury image and ending with another. I’ll get my coat, as the saying goes, and leave you to explore PRAKSIS Presents’s first issue at your leisure. We hope you enjoy our present!

YOUar

Jeremy Bailey and SHAWNÉ MICHAELAIN HOLLOWAY

Access to tools

Nina Sarnelle

Don’t rest, narrate

On art, publishing & collaboration

A tapeworm without a gut (sketches for disaster proto-fiction)

Gary Zhexi Zhang

You are safe here

Nicole Rafiki and Nicholas J. Jones discuss motivations and approaches for creating community

Climata - A hub for sound and ecology

Experiments and resources (image - Elly S. Vadseth)