Re-earthing the Weed

Johan Höglund

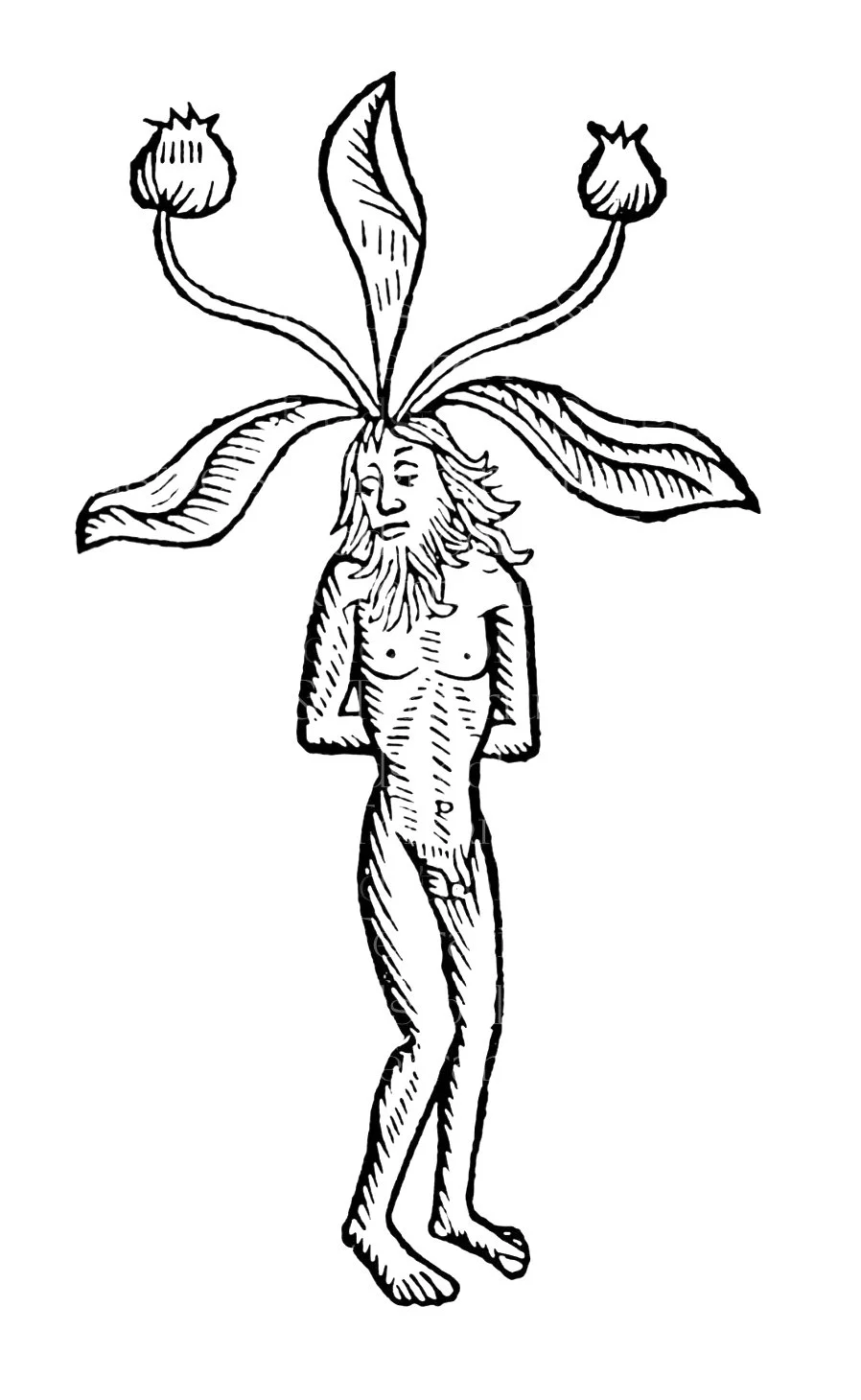

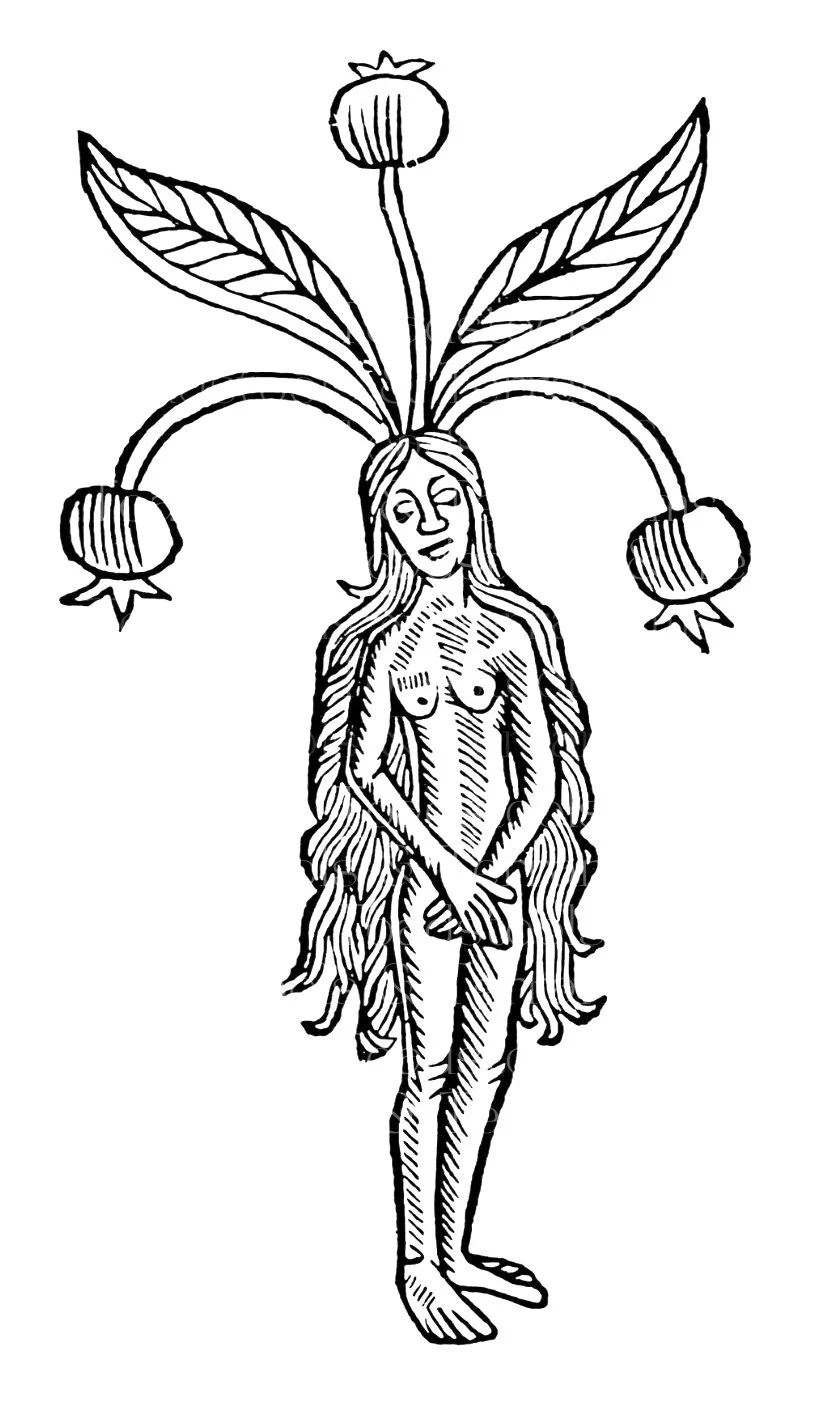

The opening scene of Sam Williams and Felicia Honkasalo’s The Unloved presents an encounter with a spectacularly Gothic and lavishly organic figure who invites us to come ever closer, to listen: great secrets will be revealed. Amidst darts of lightning and the sound of thunder unfolds a story that is at the same time theatrical and botanical. At the centre of this story grows the weed.

The Weed and the Lawn

To understand the weed, one must first comprehend its antithesis: the lawn. The lawn was introduced into human landscaping in the seventeenth century, at the dawn of what is often called the Enlightenment. This was an age when, it was hoped, reason and order were to replace the chaos and superstition of the Middle Ages. The lawn served this purpose, within an aesthetic of landscape that aimed to bring order and symmetry to the natural world. Yet, in bringing order, it also brought ecological desolation. The lawn ideally consists of only one plant species: the bladed grass. Consequently, it engages the owner of the lawn in a local war on other types of plants. The lawn is constantly thirsty; it demands fertilizers, poisons, lawnmowers—it can only flourish through the ceaseless killing of weeds. A monoculture, it is devoid of the biodiversity central to any functioning ecosystem.

As any gardener knows, life emerges from the compost heap where weeds excised from the garden are dumped. This is where microbial life that supports a fertile soil is nurtured. Just as importantly, living weeds are central to the survival of pollinators and wildlife. From early spring to late autumn and sometimes even in the middle of winter, weeds teem with colourful or invisible flowers. Their roots dig deep, nurture the soil and attract bees and other insects: food for birds that nest in trees. Weeds resist all efforts to eradicate them. They stick around because they are “fabulously good at their jobs”. This is the nature of weeds. They grow in the peripheries of gardens between gaps in the stone slabs that connect our doors to the street; they infiltrate the sward of the lawn and encroach on the walls, balconies and roofs of houses and institutions. They look towards the sun, and the moment we take our eyes off them they erupt, spectacularly. If this were not the case, it would be the end of everything. Ecosystems function not in spite of what we define as weeds, but because of them.

Monocultures of the mind

The conformity that the lawn breeds is not only ecological, it is also social and cultural. At the time of its conception the lawn signified humanity’s imagined conquest of nature, but it also coincided with the expansion of the principle of private enclosure as an essential part of social relations. This was something new. For much of the Middle Ages, most land constituted what is called “the commons”: it was communally accessible and open to all farmers to graze and tend their animals. The enclosure movement transformed this social and economic relation to the land. Suddenly, it could be owned and compartmentalised. New fences and walls were built—not to protect settled communities from raiders, but to mark the borders of property. The lawn was in step with this development. It helped introduce new ways of being, thinking and relating to land; it marked a new kind of hierarchical social system.

At the time this new social and economic order emerged, the lawn was still exclusive and rare. It demonstrated a wealth so vast you could keep part of your property empty of vegetable plots, animal pens, dung piles and uninvited neighbours. In the wake of the economic boom of the 1950s, the fenced-in lawn became ubiquitous. It still marks a certain wealth, especially in poorer parts of the world, but it serves a primary function of enfolding people into middle-class rituals and the normative hierarchies that maintain this class. It is part of a social order that emerged from the very notion that land can and must be conquered, reshaped, owned and mastered, even if the process strips it of vibrant forms of life. Bourgeois lawn fetishism helps nurture what ecofeminist Vandana Shiva (1993) has called “monocultures of the mind”: the inability to think outside the box of the business-as-usual. Just as lawns are scoured of invasive weeds, minds are kept free of those species of doubt that might suggest alternatives to the daily grind, to the accelerating erosion of both ecological and social worlds, to heteronormality, and ownership. If such species of doubt are allowed to grow and spread, the wild may start to run riot in both gardens and minds.

Now, however, the business-as-usual must be called into question. Martin Parker (2022) defines weeds as “plants which fail to co-operate with the plans of human beings”. Thus, “it is from the viewpoint of the plan that the invasion of the wild becomes a problem”. It is now becoming increasingly clear that the existing social, economic and political order, and the monocultures of the mind that uphold it, are steering the planet towards economic and ecological ruin. What Parker calls the “plan” needs to change, and that means allowing wild thoughts to invade and weeds to grow; learning to love the thoughts, longings, dreams, desires and convictions that threaten the stability of the dominant social order.

Gothic and Weeds

Weeds grow stealthily, germinating in the soil’s Gothic darkness, propagating in secret and slinking into view. They lurk unseen, underground, as roots and rhizomes. They hide in the undergrowth, only vaguely sensed, things out of place. Sometimes, as in The Unloved, their form turns out to be spectacular and even, when we cannot tell if what sits before us is human or flora, grotesque. Confronted by this hybrid being and the facts of its strange life, we may feel uncomfortable, anxious, afraid, even lost.

This is the mode of the Gothic. When the Enlightenment attempted to envelop the world in light and order, it produced shadows where dark things grew. The neoclassical palaces (and their rolling lawns) established during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, firstly in Europe and then in North America, were temples to new knowledge, prosperity and reason. They housed governments, universities, banks and the inordinately wealthy, but they were (at times metaphorically, at times literally) built on the graves of Indigenous people and relied on proceeds from New World slave plantations, mines where labourers toiled in darkness, or factories manned by children. When the Gothic emerged as a new genre of literature, art and architecture in the late eighteenth century it registered precisely this disturbing darkness, troubling the monocultures of the mind that made colonial violence seem reasonable in an age supposedly governed by democracy and equality. Gothic scholars Rebecca Duncan and Rebekah Cumpsty (2026) argue that this version of the Gothic recycled earlier Gothic images and stories from the peripheries, the places most sharply exposed to the physical and ideological violence that made the great houses possible. Thus, the early British Gothic text invited the weeds of the imperial periphery into itself, where they grew and flowered, and—on the wind, in the crannies of coat pockets, in the holds of ships—spread further across the world.

Unlike many other genres, the Gothic does not systematically conflate the unloved and the unwanted. Rather, in Gothic fiction, horror films or pulp magazines, the “weed” is allowed to take centre stage. Sometimes it is a ghastly monster that devours the agents of white, heteronormative masculinity. In his 1988 book Imperial Gothic Patrick Brantlinger outlines the role of the unloved weed as a source of dark horror, a specimen that will be violently eradicated at the grand conclusion of the Gothic text. Bram Stoker’s Dracula concludes in this way; a gang of white men, calling themselves the “crew of light”, cut down the Count’s unloved, shape-changing body. Against this, there is a strain of the Gothic which celebrates the weed’s role in binding the world together and recognises the agencies that protect and propagate it. In M. R. Carey’s 2014 novel The Girl with All the Gifts, the pre-adolescent, fungal zombie hybrid Melanie is not the true monster of the story. She is the bright weed that will usher in the future, following the fall of the dystopian, decaying militarised state that forms the novel’s backdrop—even though her kind likes to feed on human beings.

Like the weed, the Gothic does not encourage conformity. Even the stories that turn the uninvited and unloved into monsters and cast their destruction as a form of liberation necessarily have to recognise the uninvited and unloved’s presence. The Gothic world is never a place of only one species of thought, so it is only natural that The Unloved teems with references to the genre’s central texts. The best instances of the Gothic help us recognise and embrace our own hybrid natures. They invite resistance and change. They help us to rewild our imagination and our sense of self. A change of behaviour is always preceded by a change of thought. As The Unloved reminds us, “all monsters are our distant relatives after all”.

Arts of Noticing

In her book The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (2015), anthropologist Anna Tsing advocates what she terms “arts of noticing”. These are practices that refuse the perception of nature as a mere backdrop to human activity. Tsing points out that the ceaseless collaboration of billions of species is what makes life on this planet possible. These collaborations give rise to fundamentally queer, multispecies assemblages constituted by viruses, bacteria, algae, fungi, insects, fish, birds, mammals and weeds, life forms that exist only because they co-exist. Our human bodies participate in this rambunctious orgy of life-making in many different ways. We depend on these assemblages for oxygen, water and food, while acting as host to trillions of bacteria and other microbes that live in our guts, our skin, our brains—all over us. These microbes were once thought of as dangerous weeds, but without them our immune systems, and then our bodies, would quickly wither and expire. As Ralph Waldo Emerson observed in 1878, a weed is a “plant whose virtues have not been discovered”; we now know that many of the plants we think of as weeds are essential to the planetary ecosystem and even to the working of our own bodies. By adopting the arts of noticing we can come to appreciate these connections. Once we do, our understanding of the role that weeds play, the workings of the planet and the place of human beings on it dramatically shifts.

The Unloved engages us in a similar practice. Through it, we come to know the weed as an entity that secretly grows in darkness but also dazzles on stage: for example, in the form of the wildflowers that drift downriver with Hamlet’s Ophelia, or the monstrous flesh-devouring species that light up the most spectacular of B-movie horror films. Playwrights such as Shakespeare may have loved his weeds, the minor characters, but he rarely allowed them to take centre stage. In contrast, The Unloved is a figure that creeps in from the margins. No grand play can do without these seemingly peripheral figures, and no actor can resist the artificial sun that radiates from the stage lights—even if it sets them on fire.

In this work, it is both this seasoned performer and a fabulous, queer amalgamation of human and weed that beckons us, the children of the light, to come closer, and a little bit closer still, because there is a story we need to be told and secrets we must learn. We should heed the call, come closer and learn these secrets, because to do so is to practice the art of noticing: in particular, how The Unloved grows within our own selves. We must not attempt to excise this ingrowth with poison or harsh words. To do so would be to practice unforgivable, ruinous violence not just to the weed but to ourselves. Rather than pursue conformity, we should search our souls for the opportunity to love what grows in the shade and longs for release; to love The Unloved. In such love there is hope.

References

Brantlinger, Patrick. 1988. Rule of Darkness: British Literature and Imperialism, 1830–1914. Cornell University Press.

Duncan, Rebecca, and Rebekah Cumpsty. 2026. The Cambridge Companion to World-Gothic Literature. Edited by Duncan, Rebecca, and Rebekah Cumpsty. Cambridge University Press.

Parker, Martin. 2022. "Weeds: Classification, Organization, and Wilding." Organization Theory 3 (4):26317877221131580.

Shiva, Vandana. 1993. Monocultures of the Mind: Perspectives on Biodiversity and Biotechnology. Zed Books.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton University Press.