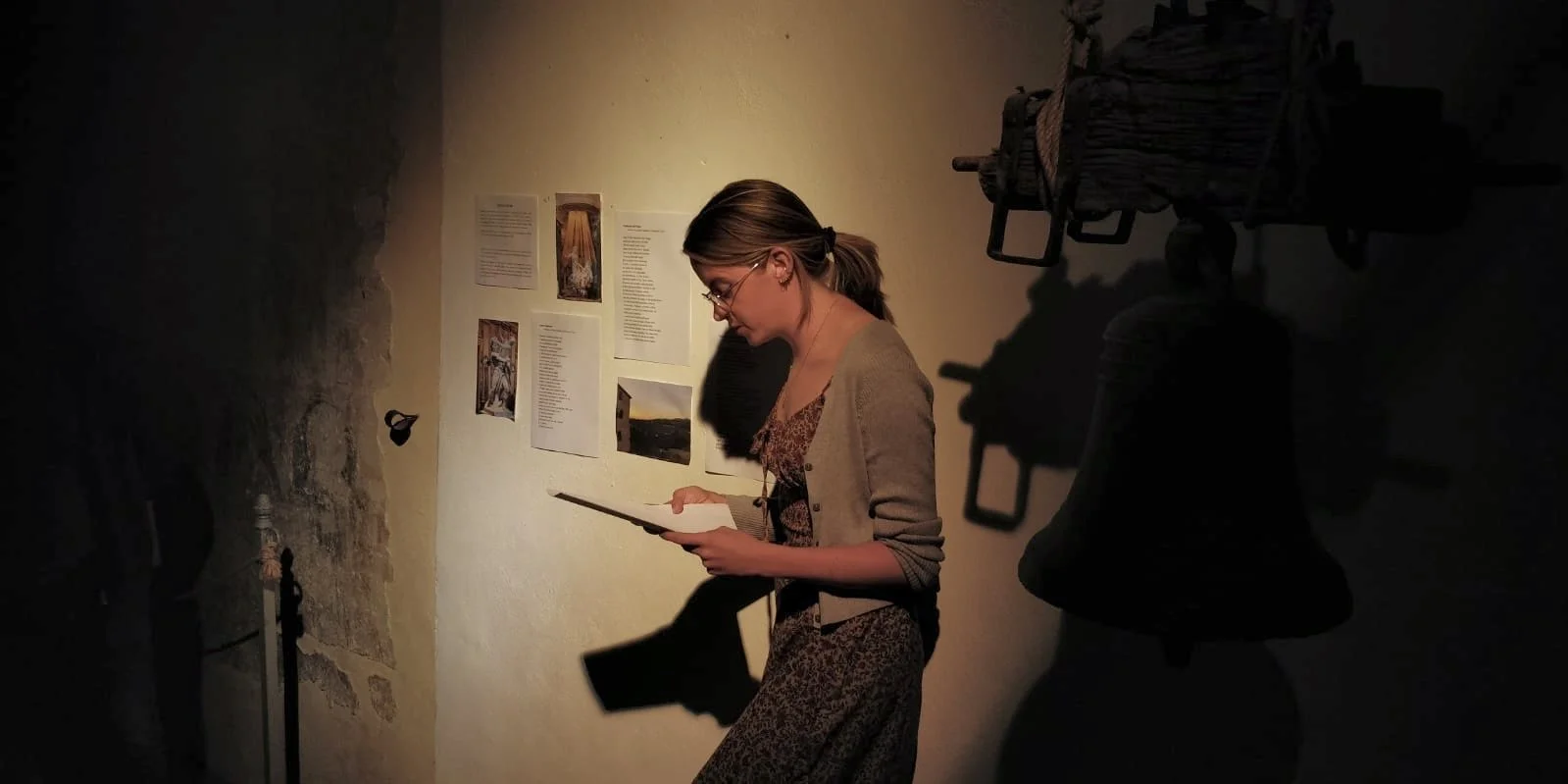

From the Illinois Test of Psycholinguistic Abilities (ITPA) taken by Mollie O’Leary during a visit to the archives of the University of Oslo

Poet Mollie O’Leary speaks with aspiring writer and PRAKSIS trainee, Alexa Zsigmond, about the subject of memory, its influence on her poetry, and ways in which her creative process combines subjective and scientific approaches. She also looks back on her experience as a participant in PRAKSIS’s twenty-third residency, Understanding Intelligence (2021).

Alexa Zsigmond (AZ): What first inspired you to write about memory?

Mollie O’Leary (MO): When I was trying to come up with a theme for my postgraduate thesis project, I kept returning to the concept of memory. I was partly interested in memory because I had a deep fear of forgetting things from my past. The erosion of memory over time is a natural process, but I felt I had already forgotten a great deal from my childhood. Because there were so many gaps, a linear progression in my mind from childhood to adulthood seemed missing, and that was destabilising to my sense of self. I feared that if I didn’t record and preserve my existing memories I would lose any clear connection to my past self: it was almost as if I was leaving her behind. I know that might sound strange, but as I researched the brain and memory, I learned that the feeling of being separated from yourself across time is a common feature of traumatic experience. This connection between trauma and discontinuous memory provided a helpful framework that enabled me to explore my own childhood memories in an informed and scientific, as opposed to purely emotional, way.

AZ: The PRAKSIS’s residency you contributed to was connected with the University of Oslo's research project, Historicizing Intelligence, an investigation into changing definitions of intelligence and their social and political effects. How has that type of academic and scientific research influenced your poetry and your understanding of creative writing?

MO: It has influenced my creative process a lot, particularly when I was writing the poems in The Forgetting Curve (2023). A particularly important academic source was writer and scholar Lewis Hyde's A Primer for Forgetting: Getting Past the Past (2019), a book that explores the historical, mythological and cultural importance of forgetting. Academic sources have also helped me to better understand the neuroscience behind memory, and the research that’s been done on trauma’s impact on the brain's ability to remember. A basic discovery that had a big impact on me was the simple fact that the brain is designed to forget. A certain amount of forgetfulness is a sign that your brain is functioning properly. Without forgetting, there would be no memory. This discovery took away some of my shame and fear around forgetting things because it reframed forgetting as something other than a deficit or defect.

My research into theories of trauma also suggested that the ability to integrate past experience into a coherent life story is essential in terms of maintaining a stable sense of self. This partly explains why trauma can be so disruptive and dissociative. Traumatic memories are stored in the brain as isolated flashbacks and sensations that don't fit into a clear narrative of the self. Being able to reassemble these memories into a story has the potential to be very restorative, partly because it allows us to re-establish a sense of agency and ownership over those experiences.

AZ: One of your aims for the PRAKSIS residency was to explore ways in which memory connects with ideas of intelligence. Can you say more about that?

MO: Memory and intelligence are often connected via concepts of memorization and factual recall: having a strong memory is often viewed as a sign of intelligence. However, many factors other than intelligence shape our memory, and our understanding of intelligence is also shaped by many factors. To give an example, a child who is experiencing elevated stress is more likely to forget things than one who is not. This may well result in their achieving lower grades at school, but to say this is a reflection of a lower level of intelligence would be inaccurate.

During the residency we spent a lot of time analysing concepts of intelligence and asking which groups have historically shaped the definition of intelligence, and I've thought about both these things a great deal in my poetry. We examined an archive of different intelligence tests, including the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children and the Illinois Test of Psycholinguistic Abilities. Looking at these tests and the ways they are written greatly interested me, partly because I've employed phrases and formats from various intelligence tests in my poetry. For example, I have a poem written in the same multiple choice form as a verbal reasoning test, and another poem that is written using logical propositions. I like adopting elements such as these from intelligence tests because their rigidity emphasises the strangeness of using the formulas of a test to reflect our life experiences, feelings, and thought processes. I don't say this to disprove the utility of the tests or to argue that all testing is bad, but rather to highlight their limitations.

AZ: During the residency, you were in dialogue with people who have different professional backgrounds from your own. How did you find this interdisciplinary situation? Did your encounter with a range of perspectives and approaches help?

MO: I loved working with artists from different backgrounds. My work is focused on language and text-based projects, while most of the other residents make work that is largely visual, and so they pushed me to notice and think about things I normally wouldn't consider. I collaborated with Hana Yoo, who primarily works with visual mediums, to create found poetry using language from the tests. Seeing the way she incorporated images and colours in her poetry helped expand my understanding of what found poetry can be, both textually and visually. Informal conversations over dinner with Charlie Harrison, the interdisciplinary artist who I shared accommodation with, always resulted in cool new ideas. I really appreciated the insights I gained into the ways that stories can unfold through sculpture, video, painting and other visual media.

AZ: Has the residency influenced you and your writing? If so, in what ways?

MO: Yes, the residency has impacted me in many ways. It was inspiring to spend an intensive period of time with artists who prioritise their practices in everyday life and pursue art as part of their full-time job. I love being a poet, but it can be disheartening at times working in a country, the United States, where the arts are not always well funded or taken seriously. In all those ways, spending time with the other residents was really uplifting.

AZ: Could you share one of your poems that is connected to memory with us?

MO: I’m happy to. This one is titled Recurrence:

Peering into the scoured bathtub, I spot

sour mildew budding. I wake to pink biofilm

on graying porcelain. Even slime mold has memory;

its amoeba body retrieves oat flakes. After I scythe

seven inches of hair, still I feel long strands running

down my spine. Ever since the flood, I try not to hold

onto much, exfoliate dead cells as if this excess

might weigh down a life raft. I slip pale sea glass

into my pocket only to part with it once I reach the car.

I used to capture wild hermit crabs, place them

in salted tap water, swooshing the tupperware

to mimic waves. I thought I could trick them

into being home. The hermit crabs lasted a day,

leaving behind their tiny calcified capsules, perfect

like piped frosting. The brain wants to be buoyant,

shedding ghosts to avoid overgrowth. We’re meant

to slough off the past, but I still don’t know

where to keep the shells the tide gives back.

Mollie O’Leary is a poet from Massachusetts. She holds a B.A. in English and Philosophy from Kenyon College and an M.F.A. in creative writing from the University of Washington. Mollie’s chapbook The Forgetting Curve was published in 2023 by Poetry Online. Her work has appeared in Frontier Poetry, Chestnut Review, and elsewhere. In addition to participating in PRAKSIS, she has also attended artist residencies in Mexico and Italy. Find more of her work at mollieoleary.com.

Residency 23, Understanding Intelligence took place in late 2022. It invited a multidisciplinary group of artists, scientists, and others to explore concepts and constructs of intelligence. It was developed with Ageliki Lefkaditou, Sophia Efstathiou and the Museum of University History, a department of the Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo. Find out more here.