Gold, Ashes, and Fingernails

Nanna Melland’s Decadence and Renaissance

By PRAKSIS Presents editors

She works with materials such as fingernails, pigs’ hearts, orchids, miniature atomic bomb rings, laser-cut aluminium airplanes, polypore fungus, and used intrauterine devices (IUDs), turning familiar objects into forms charged with bodily, cultural, and existential resonance.

Melland studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, completing both a diploma and being appointed Meisterschüler. She is a trained goldsmith with a journeyman’s certificate, and also holds a Candidata Magister degree in Social Anthropology, the History of Religion, and Tibetan language from the University of Oslo. Melland received the Norwegian Association for Arts and Crafts Main Prize in 2008. Her work is represented in the Nordenfjeldske Art and Design Museum, Trondheim, and has been exhibited internationally at institutions including the Pinakothek der Moderne, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, and the Museum of Arts and Design, New York.

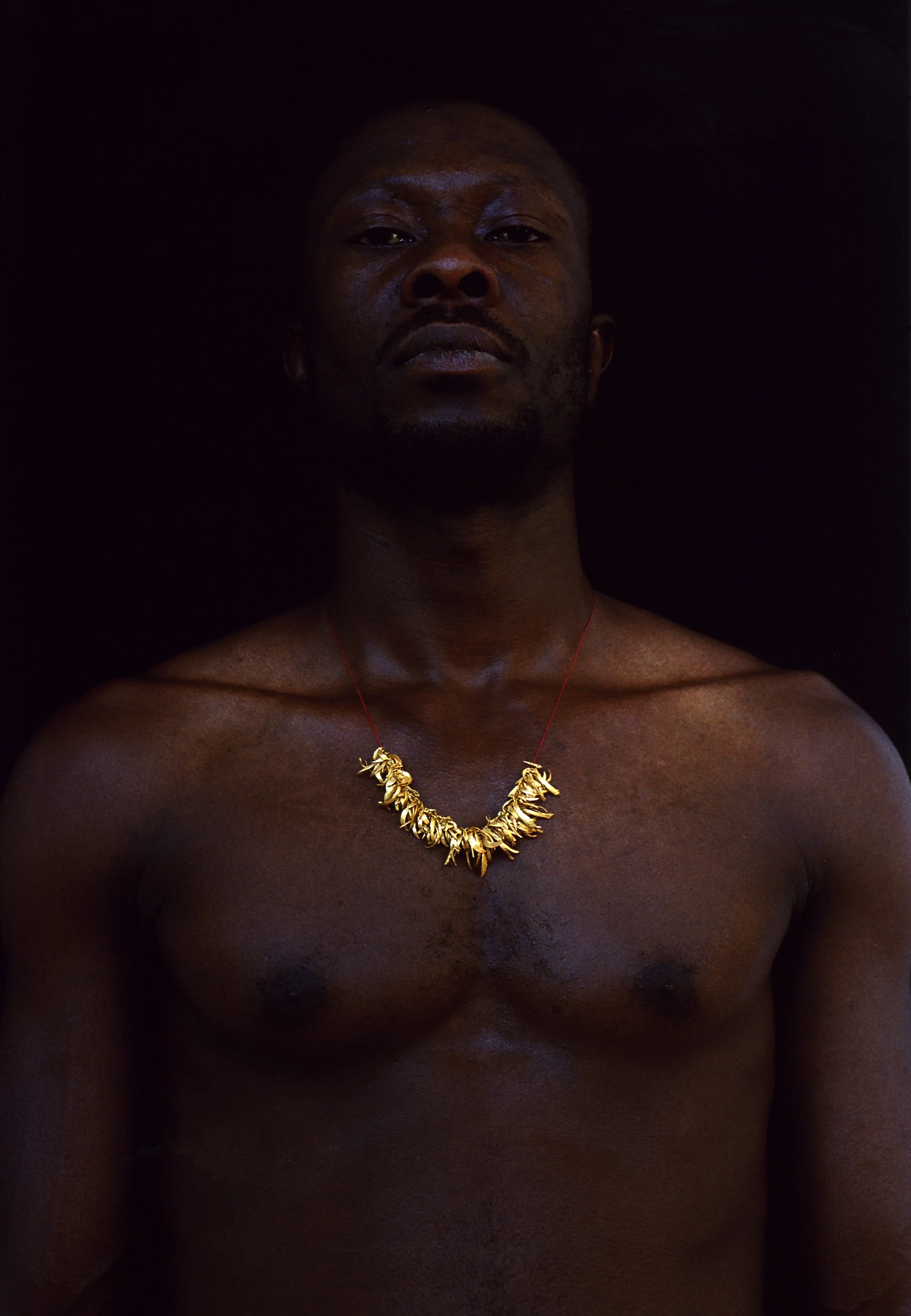

Nanna Melland, Isak with Decadence

Nanna Melland, Herr Öckel with Renaissance

In craft practice in general and jewellery in particular, it is relatively unusual to find artefacts that set out to create deep ambiguity, self-reflexivity and critical interrogation around their categorial status, value and meaning: each made object’s purpose, significance and intended aesthetic is usually relatively legible. This is even the case in most conceptual jewellery, a category which dates back to the 1960s. All too often, the “concept” informing the piece turns out to be an easy read, or at worst a gimmick designed to enhance the crafted artefact’s salability. Within the British Academy of Jewellery’s website, for example, “concept” is mistakenly conflated with “artist’s statement”, and the conceptual piece is characterised as the maker’s encoding of an intentional “message”, a kind of semaphore to be deciphered by the made item’s wearers and viewers (BAJ.ac.uk). Nevertheless, there is nothing intrinsic to jewellery making to prevent its engagement with conceptual criticality. Exactly like “fine” art, contemporary designer jewellery tends to connote high commodity status and aesthetic redundancy (its “use” is to be aesthetically pleasing, not functional); in significant respects, art and jewellery making share the same predicament. The work by Nanna Melland featured here address this situation head on, demonstrating jewellery making’s capacity to act as a critically self-reflexive, conceptually driven, process.

Both Decadence, (2001-2003), and Renaissance, (2001-2004), have involved the complex crafting of necklaces from cast metal fragments, reproductions of Melland’s own toenail and fingernail clippings. Decadence has been executed in high-carat gold, and Renaissance in shibuichi, an ash-coloured silver and copper alloy that was historically used in the making of samurai sword fittings. Strung on slim threads of red (Decadence) and dark grey (Renaissance), the cast clippings are elevated from abject detritus to sophisticated adornment: recognisable as nail fragments, but only just. Melland has described the earlier work as a “philosophical proposition” that asks, “what happens when what we discard becomes precious? When the grotesque becomes desirable?”, questions arguably also posed by the later piece. The two interplay with one another in ways that expand and destabilise the readings of both, posing “uncomfortable but necessary questions” about gender and race, “value and decay, attraction and repulsion, luxury and loss” (Melland, 2025).

Historically, a key characteristic of conceptual art is the generation of radical uncertainty as to the “location” of the work, and this is also true of Melland’s paired artworks. Their discourse unfolds via photographic as well as craft and research processes: the individual necklaces feature in two carefully staged photographs featuring human models whose collaboration with Melland further complicates our understanding. Decadence is modelled by Isak, a Munich Academy of Fine Arts employee of Ghanaian origin, and Renaissance by Herr Öckel, another Academy employee and Bavarian local. At first glance the muscular bodies of both connote masculine power. However, we learn from Melland that as Isak modelled, he was managing the effects of terminal illness; and when we examine Öckel’s face our eyes are attracted to the (mis-named) “triangle of sadness” between his eyes, creases that softly suggest lived experience, the interaction of body and emotion. Dialectics of power and vulnerability, vitality and mortality, emerge, undercutting masculine stereotyping and drawing out a certain irony in the “luxury” nail-necklaces. Discarded bodily matter wishfully immortalised in precious metal, they take on the pathos and urgency of the talismanic. Writing on the project, Melland aligns her transmutation of bodily waste with the Decadent movement’s love of “artifice, ornament and indulgence” (Melland, 2025), an association that compounds the dialectic: after all, for the extremists of Decadence, artifice, ornament and indulgence were (at times literally) matters of life and death.

Melland’s choice of a white and a Black model in the two images also, obviously, compels attention. In her written reflections she subjects her photographing of Isak wearing Decadence to an unsparing analysis. Any celebratory association of his wearing of the golden necklace with Ghanaian heritage (the Asante kingdom, with its gold-based economy, occupied much of present-day southern Ghana) is necessarily undercut by the historical facts of colonial “extraction, exploitation, and economic violence”. Further, the relations of looking in the photo repeat “a conventional trope: the [presentation of a] hyper-visible, idealized Black male body” in an image made by a white person (Melland, 2025). Melland acknowledges the risks in her strategy, but states her intention to “turn… the gaze back on itself [and] ask… who gets to look, who gets to be adorned, and at what cost”.

The creation of Renaissance—as process, object and image—further complicates that critical challenge. Melland’s commentaries make clear that both Isak and Herr Öckel’s images conceal as much as they reveal. In the later photograph, Öckel’s bodily adornments other than the Renaissance necklace—his single earring and tiny tattoos—are now universal and mobile as signifiers of class and culture; they frustrate rather than facilitate any visual quest for “identity”, a lesson we are invited to refer back to the earlier photograph. And finally, there is the enigma of the relation of the two necklaces: decadence portrayed in glowing gold, and a strange “rebirth” that is the colour of ashes. Across these works, Melland demonstrates and explores jewellery’s capacity to operate conceptually—not to telegraph a pre-packaged (we might say, commodified) “message”, but rather to release the work’s own meanings: to allow it to challenge, trouble and expand the understanding of its viewers, including that of its maker.

Nanna Melland, Decadence, necklace, 2001 – 2003,18 ct gold, cire perdue[1] cast finger and toenails, linen, Ø 50 cm

Decadence, detail

Renaissance, detail

[1] Cire perdue (French for “lost-wax casting”) is a metallurgical technique with a very long tradition, documented as early as the third millennium BCE in Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, and ancient Egypt. The process involves modeling a form in wax, encasing it in a refractory material (such as clay or plaster), and then heating the mold so that the wax melts and drains away. This leaves a cavity that is then filled with molten metal. The method allows the creation of highly detailed and complex objects that would be difficult or impossible to produce using other techniques. Lost-wax casting has been employed in various cultural contexts, including ritual bronze vessels in ancient China, the Benin Bronzes of West Africa, and Renaissance sculpture in Europe.

[2] Shibuichi (四分一) = “One quarter” – refers to the classical alloy of 1 part silver and 3 parts copper. Variations exist, but typically 25% silver + 75% copper. After patination (with rokushō), it develops gray to silver-gray or bluish-gray tones, depending on the silver content.

Traditionally used for decorative inlays and contrasting surfaces, especially on sword fittings, but also in contemporary jewellery for subtle gray shades.