Zehra Doğan’s Haunting Visions of Incarceration

Kaya Genç’s written account of Zehra Doğan’s work highlights both its oozing corporeality, and its power to connect with bodies elsewhere and transcend the physical bounds of imprisonment within which it was created.

In 2017, the trailblazing Kurdish feminist artist Zehra Doğan made a digital tablet drawing of a photograph of Turkish soldiers posing with machine guns. At the time, Doğan was a 27-year-old reporter who had already served time in prison because of her political activities. She founded Jinha, a feminist news agency, and covered the human rights violations of the Turkish military in the country’s Kurdish-populated east. Her physical experience of Turkey’s war zones defined her future practice. In the background of Doğan’s 2017 drawing was Nusaybin, a city reduced to rubble by crossfire between Turkish soldiers and Kurdish militants. The city’s ruins are shown ominously peppered with crimson Turkish flags. In the foreground, Doğan drew shadowy security personnel who resemble scorpions. The image landed her behind bars once again, after a court ruled that it constituted terrorist propaganda.

Between 2017 and 2019, Doğan’s representations of her own body and those of other female cellmates helped her to metaphorically melt and surmount the walls of Diyarbakır prison, where for two-and-a-half years she was held captive by the Turkish state. Her works used materials amassed inside prison cells to embody rather than simply represent incarcerated people. Doğan resists the hegemonic order by painting with corporeal substances— for example, using a paintbrush made out of the hair of her fellow prisoners, or employing menstrual blood, a suppressed subject and substance in Turkish public life, to articulate the unimaginable violence conducted in eastern Anatolia (another taboo that the state attempts to make invisible). These corporeal tactics allowed her and her cellmates symbolically, at least, to escape the chains of Turkish autocracy.

Doğan left Turkey in 2019 and in the same year presented her work at Tate Modern: “Left Behind,” an exhibition of objects she’d found in the debris of war-torn Kurdish cities. Before this, though, Doğan was incarcerated in three locations: Mardin in 2016, Diyarbakır in 2017-18, and Tarsus in 2018-19. Confinement provided her with the essential material of her artistic practice. Alongside brushes made from the hair of her imprisoned comrades, she has used feathers from birds that nested in the barbed wire of their exercise yard and paints which incorporate other substances from prison: cigarette ash, coffee, pepper, bird droppings, cooking oil, pomegranate peels, the blood of birds, honey and aspirin tablets. Just as her media are derived from basic, collectively available substances, her practice also projects a sense of collectivity, rather than the individual anger of an isolated embodied subject. She was part of a collective of bodies that stood for historical discontent while struggling to survive appalling prison conditions. In her works, figures climb, grab barbed wires, dance and lie on their back in courtyards, suffering the frustrations of constant surveillance. Scarves, cardboard packaging, towels and tinfoil serve as canvases for these compositions.

Doğan’s prison diary, The red army in my pants, was made in 2016, when the artist lived in Mardin prison. It depicts a woman bleeding from her uterus. The artist used ballpoint pens, juice from rose hips and a cloth fabric to produce this six-page, 65 x 83 cm, work. It features a letter written in Turkish that begins with the phrase, “My eggs are splitting”, and articulates a sense of deep frustration: “I want to throttle anyone who stands in my way”. This is accompanied by sketches of a protean female body that resembles an avenger: naked and unapologetic, she menstruates in pain and ecstasy. The red of the rose hip juice adds an ambivalent symbolism to the otherwise black-and-white composition.

This avenger figure, ecstatic in her fury yet liberated in her captivity, returns in other works by the artist. While staying at Diyarbakır prison in September 2017, Doğan created Uproar by applying menstrual blood on paper. In this dreamlike composition, a group of naked women circulate within a nondescript space. Surrounding them are forms that may be either trees or walls. Despite their eternal confinement, the figures seem paradoxically free. Menstrual blood colors their naked bodies. Within the work Doğan chronicles and transforms her prison life, turning a death sentence into a carnivalesque vision, and her use of her own blood turns her menstrual cycle into a marker of the passage of time—another month, otherwise indistinguishable from the one before, has passed in confinement.

Doğan has increasingly mobilized satire and grotesquery and embraced the carnivalesque in her works, which have survived through careful strategizing. She drew on dresses sewn by her mother, or used material that she stole from the prison storeroom. The dresses and textiles escaped the prison walls by being delivered to relatives as dirty linen. Overflowing of the malediction is an example of a work made on a dress and was produced while Doğan was incarcerated at Tarsus prison in 2018. Made using a felt pen, hair and menstrual blood, the work is drawn on a dress decorated with polka dots, and depicts two naked women seen from the back. They eye each other and seem aware of being surveilled. Menstrual blood trickles down from a hand-shaped blot on the upper side of the dress and drips onto one of the seemingly docile figures, suggesting a looming catastrophe.

Doğan has emerged as a defining artistic voice of the violent, repressive post-August 2014 period in Turkey because of her defiant use of art to transcend her bodily captivity. She has made art from her bras and briefs and represented female heads and vaginas using her own hair. Her portraits of ghost-like faces with shaven heads will continue to haunt, terrify and inform. Rich in poetic potential, Doğan’s work will inspire further transmutations between spaces of incarceration and incarcerated bodies. It is a popular refrain among Turkey’s progressive communities that the country feels like an open-air prison, but Doğan’s aesthetic is not confined to prisons. Her works will continue to embody a collective desire, hers and ours, to articulate and transform the continuing corporeal violence of life under Turkish autocracy into novel and powerful visual forms.

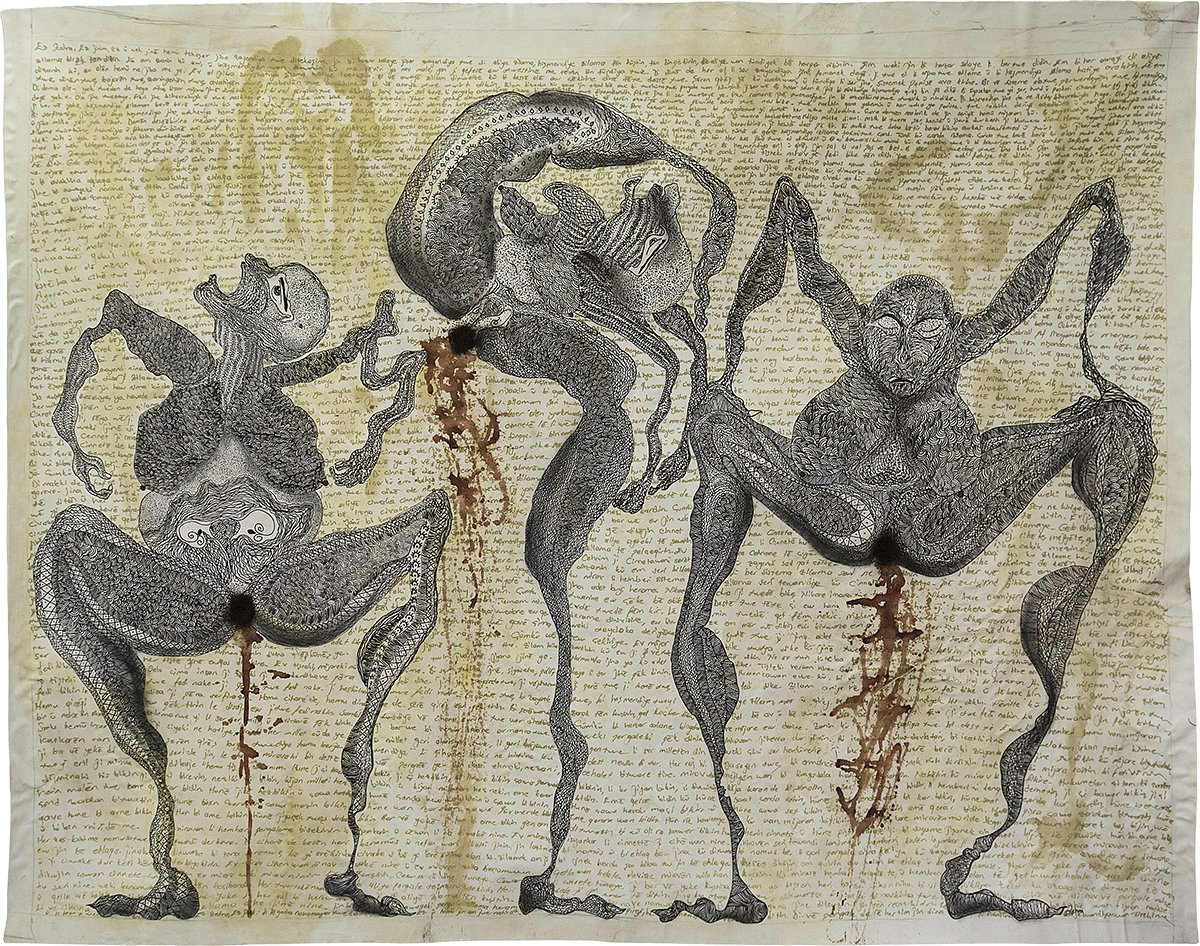

The red army in my pants – 2, 2020. On canvas, felt pen, pastels, turmeric, menstrual blood, hair, 164 x 205 cm. Photo: Ludovica Magini. Prometeo Gallery, Milano

Kargaşa (Uproar). 14,5 x 21 cm. Menstrual blood, pencil, on paper. 9.2017, Diyarbakır prison

Toqa Lanetê (Overflowing of the malediction) 230 x 135 cm. Felt pen, hair, menstrual blood. Tarsus prison 2018