Fictioning Comfort and Other Strata of Rotterdam

Golnar Abbasi and Natasha Marie Llorens talk about resources, precarity, potentiality and more.

Natasha Marie Llorens: In the interview with Kris and Eloise, you talk a lot about redistributing resources and how that is an important part of the way you position yourself both within Sarmad and as someone working with artistic education in the Netherlands. How did consideration of resources become a crucial part of your process? When did you get politicized about this?

I also know from working with you that you work as if there is no money involved, with this kind expansiveness and unhurried curiosity towards the things you pay attention to. So, I wonder if you can unfurl the relationship between resources and positionality in your work as a curator—however you are defining that right now?

Golnar Abbasi: Firstly, this commitment to thinking about resources is deeply rooted in my embodied experiences of precarity, grounded in my past years’ work on changing forms of labour, the crisis of precaritisation and the politics of living-working in extractive processes and contexts. Thinking about access and resources in spaces of (living and) working is an extension of that sensitivity to the forms of (structural) exploitation that we experience in precarious jobs, homes, or citizenships. Institutional (infra)structures are part of this thinking, and underline the urgency I feel about the distribution of resources. They condition the ways in which we understand and relate to other people and their labour. These infrastructures condition how resources and access are distributed, fortified, opened up, enclosed, expanded or extended.

Secondly, I realized that migrating across geopolitical borders—and moving across strata of privilege and precarity as a sociopolitical consequence of that migration—is part of an experience of violence that conditions my sensitivity. Being a curator with a direct relationship to institutions and their resources, allows for negotiation about the distribution of access. And the experience of precarity, of occupying a position outside of fortified enclosures of comfort, fosters sensitivity to the invisible labour of negotiating access. This invisibility of the negotiation work is especially critical in display economies—such as the economic world of art—whether in art exhibitions or education.

For me this interest in the logistic and administrational aspects of work is evident in and learnt from self-initiative projects and practices. I realized that if I wanted to show or display work or make conversations, without a lot of prior access to resources or people, I would just have to do it myself. You just make the space; make the books. This is something I learned from working in informal economies as well, like in self-publishing, where there is a rich economy of skills and discourse around how to acquire resources, how to subvert institutional access gates, how to leak resources out, etc.

NML: The bike messenger project really marked me, it was called Fictioning Comfort. I won't gush about it here, but what really struck me is that these things—papers, cushions, books—came to the apartment I was living in at a moment in the pandemic when I really needed that kind of contact. They reminded me that meaning was still being made in the world, even though it was almost impossible to be in contact. I wonder how that project relates to Rotterdam? Who ended up on the delivery list and why? Whether it changed your understanding of your own positionality in the city or grew out of that positionality? The project fit Rotterdam so well as a gesture in time and space, and I wonder how you came to it. I wonder how much you have to commit to a city to make a gesture as meaningful as that one was, one which responds so perfectly to the circumstances?

GA: For Nowruz under covid lock down, my partner Arvand Pourabbasi and I wrote letters to friends and delivered them on bikes. This idea of connecting to people despite the crisis leaked into our professional context when we had to figure out how to curate the show—Ficitioning Comfort —under lockdown. Lockdown did not only mean no studio visits or meetings, but it reoriented our curatorial thinking around comfort and exhaustion: how to do this work in a moment of deep crisis? What comes of work commitments when all our priorities have been rearranged? More than before, doing this show was about reimagining how we relate to people and their labour with a deeper sense of commitment.

The show created a larger network beyond our (curatorial) relations. Artists invited collaborators, people got involved in production of an online show, etc. This larger network constituted the delivery list. The rounds of bike messenger deliveries, which lasted for eight weeks (two deliveries per week) before the opening, were a way to extend the space of the project. Tomi Hilsee, the bike messenger, had worked professionally in that capacity in the U.S. They provided access to the history and culture of bike messengers, which allowed us to think together about the admin and logistic work that makes larger formal procedures possible, but which also exists in its own subterranean space. Here, it was a gift economy: a “networking” / distribution that was intentionally slow and affective, one that did not remove itself from the experiences of precarity that we were living through, or the political question(s) at hand.

Lastly, I think a part of this commitment to Rotterdam might come from an attempt to find a home in a state of eviction from other homes. There is a sense of commitment that emerges from the precarity of migration. It matters how we come to settle in spaces; it conditions our intentions to work, connect, engage, make kin. For me there is an aspect of this fortified comfort, of coming to settle in Europe and dealing with constant evictability, that shapes the political question of the spaces and people that hold us.

NML: So much of your practice is involved in making spaces where people can show up together and pay attention to things that go against the grain of cultural capitalism. I wonder if (and how) you think about this place-making work within the arts as activism? Does the structural instability of your position makes the arts-organizing work that you're doing more urgent?

GA: I hesitate to call this activism. I think these are two different spaces, each fortified with their own economy. Different sensitivities exist in either space; some conversations are easier to be had where critical thinking is part of the given or expected discourse, and some happen more in space in which radicalisation is a practical norm. Evictability conditions one’s priorities and shifts how one navigates (or is given access to) these spaces. Art, activitism, and their respective resources can be used, in turn, to make space to collectively pay attention to other things. This is what keeps me interested in (both of) these spaces. That it is possible to operationalise access and mobilise resources for anti-violence practice and urgent causes. Making space means, in part, working through the logistics and admin of existing spaces; to extend and expand resources, organisationally rearrange, re-articulate how things can be made public. This commitment to strategy, against the grain of cultural capitalism and its identity-oriented attention economy, sometimes also makes it impossible to open space for an anti-violence conversation.

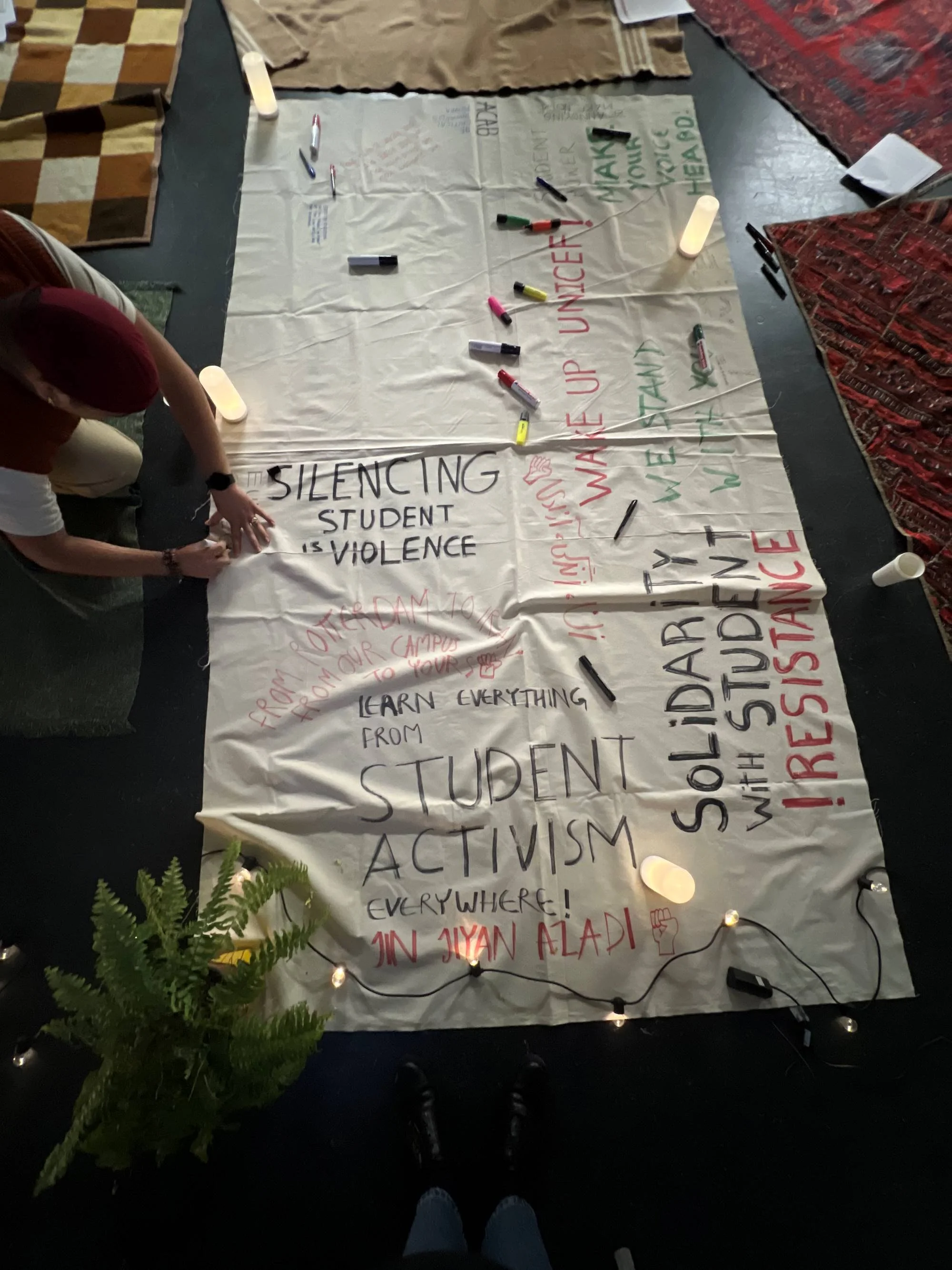

I am specifically interested in student activism and the spaces that it can create, which I see as a kind of radicalism and commitment that operates on its own grounds, in its own nameless and faceless economy. I realise this expansiveness might be due in part to the fact that the precarity crisis that conditions professional spaces in a more existential way than art education (and it is our responsibility to show that to our students). But I find students’ generosity with their time, attention, and other resources through their activism to be incredible. The cultural-political practice that student activism models for us is intense in its strategic commitment to the work, to anti-violence causes, as well as to kin making and space making. We have everything to learn from our student activists.

Bike Messenger Round Roffa. Incomplete collection of things accumulated at Dispatch including: dispatch contact sheet; notebooks made out of scrap paper at dispatch; box of tea; zine on Fast Eddie made by Tomi Hilsee; Calendula seed bag grown by Alireza Abbasy; Rotterdam food map initiated by Amy Suo Wu; tiles made by Pendar Nabipour; receipt zine by Florian Cramer; bowls received from Clara Balaguer; yellow notebook and tea from Ying Liu, among more letters and poems and things.

Bike Messenger Round Roffa. Messenger showing and discussing carpet pattern tiles from Iran on the porch of a receiver’s home, kept unfolded and flat by the weight of cushions made by Maike Hemmers. June 2020. Photo by Tomi Hilsee.

Fictioning Comfort Closing Weekend online event under covid lockdown, Convo 2: Sami Hammana in conversation with Alireza Abbasy about his work (Eyn Eyn Eyn Stories). 12, September 2020.

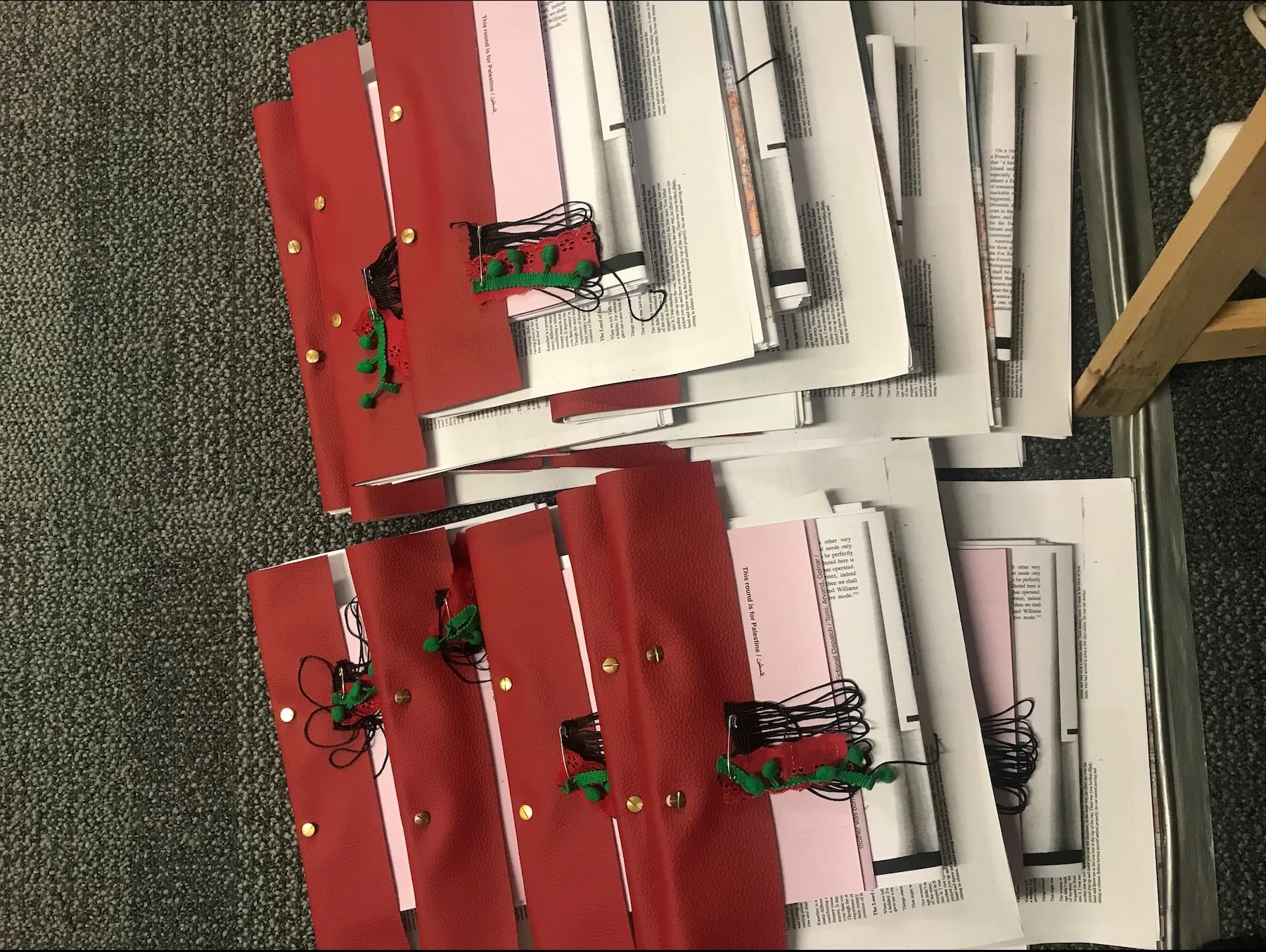

Bike Messenger Round Roffa. “This Round is for Palestine / فلسطین” publication made by Dispatch of copies of existing work on Palestine. June 2021.

Bike Messenger Round Roffa. Delivery of resistance ritual prompts and a roll of print wallpaper piece made by Arvand Pourabbasi. Photo by Tomi Hilsee. June 2020.

Student activism banner at Willem de Kooning Academie & Piet Zwart Instituut, Rotterdam, together with student collectives WdKA Spin and WdKA Haven. December 2020.