An anthology of art & ideas

Eds. Rachel Withers and Nicholas J. Jones

Issue 9:

Now & Always

—Material Translations

Spring 2024

Guest edited by Merve Ünsal

Superficially put, translation is the act of making a text legible in another language. The text appears to change form as it transitions from one language to another, and this could be seen as a process of shapeshifting, transfer or interpretation. However, when the mechanisms of the translation method are deconstructed, both the “original” and “translated” texts become nebulous, and the temporality and location of translation expands beyond the limitations of either text. What emerges is an idea of translation as an ongoing and constant intervention. Translators need to recognize and express the “reciprocal relationships” between languages,[1] and because texts are alive, translations also need to renew themselves through language to remain living.[2] Only by letting go of precise meaning, and identifying language as a site of and a search for truth—a passage, an arcade, a space of movement—can a translator allow the original work to shine through the translation.

Scholar of translation Theo Hermans has proposed that translation is both an instrument and a context; it is a cross-temporal, cross-lingual, and cross-cultural process that is necessarily plural, polyphonic and transitory. His ideas help us reflect on translation as both a method and a state.[3] Hermans uses a term coined by Kwame Anthony Appiah, “thick translation”, to describe the work of approaching another culture. Appiah’s term was itself derived from Clifford Geertz’s phrase “thick description”, a characterisation of the work of ethnography. Hermans is interested in the double dislocation made possible by thick translation. He suggests that translators poke at unfamiliar cultural materials with tools that are themselves not fit for purpose: they have emerged from the familiar to consider the unfamiliar, making them inadequate from the start.[4] Hermans’s concept of thick translation thus leads to various crucial questions. If the production of tools to make precise and accurate translations is an impossibility, why translate at all? How do we translate responsibly? Might there be ways to engage in translation as a self-reflexive and perpetual process and method?

In response, a translator might seek to develop tools to look at the “other” which self-reflexively consider the pitfalls contained in the assumptions from which they arise. Translation of this kind would become disembodied. It would shed its languages and texts, responding instead to the urgent need for immediate, profound change. The world is on fire; the state of exception has always been here and is here to stay, as we have learned from the tradition of the oppressed.[5] When we recognise that the undercurrent of history is not a smooth continuum punctuated by exceptional events, but a permanent state of crisis, [ruptures of exceptional moments but as appearances of such moments arriving and dissipating] the illusion of inside and outside, now and not-now, I and non-I disappear—we are always in translation, now and always.

The works included in this issue of PRAKSIS Presents are all based in self-reflexive research into geography and the body. They respond materially to this situation by embodying tensions between materials, languages, contexts and places, and existing in a flickering state of perpetual translation. Ceylan Öztrük traces the bounds of architecture through attempting to melt into her institutional holdings, while Salwa Aleryani uses the shifting materialities of her objects as negotiations with, and ultimatums to, histories. Banu Çiçek Tülü treats the urban space as a site of collective intervention through her soundwalks, and these resonate with Nazli Koca’s swift movements within urban spaces—movements interwoven with dream images that appear to taunt each other. Kaya Genç’s written account of Zehra Doğan’s work highlights both its oozing corporeality, and its power to connect with bodies elsewhere and transcend the physical bounds of imprisonment within which it was created. Bradford Nordeen’s invocation of Diamanda Galás’s presence also brings temporary assemblies of bodies to life again: collectives merging in performances that are anchored in profound old memories, even as they give birth to powerful new ones.

___

[1] Walter Benjamin, “The Translator’s Task,” trans. Harry Zohn, in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, 1968), 72.

[2] Ibid, 74.

[3] Theo Hermans, “Cross-Cultural Translation Studies as Thick Translation,” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 2003, Vol. 66, No. 3 (2003): 382.

[4] Ibid, 385-386.

[5] Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” trans. Harry Zohn, in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, 1968), 257.

Square Edges of a Round Room

Ceylan Öztrük traces the bounds of architecture through attempting to melt into her institutional holdings

Who Rotates Around Whom

Salwa Aleryani uses the shifting materialities of her objects as negotiations with, and ultimatums to, histories

Blocking The Sound

Banu Çiçek Tülü treats the urban space as a site of collective intervention through her soundwalks

any-space-whatevers

Nazlı Koca record swift movements within urban spaces—movements interwoven with dream images that appear to taunt each other

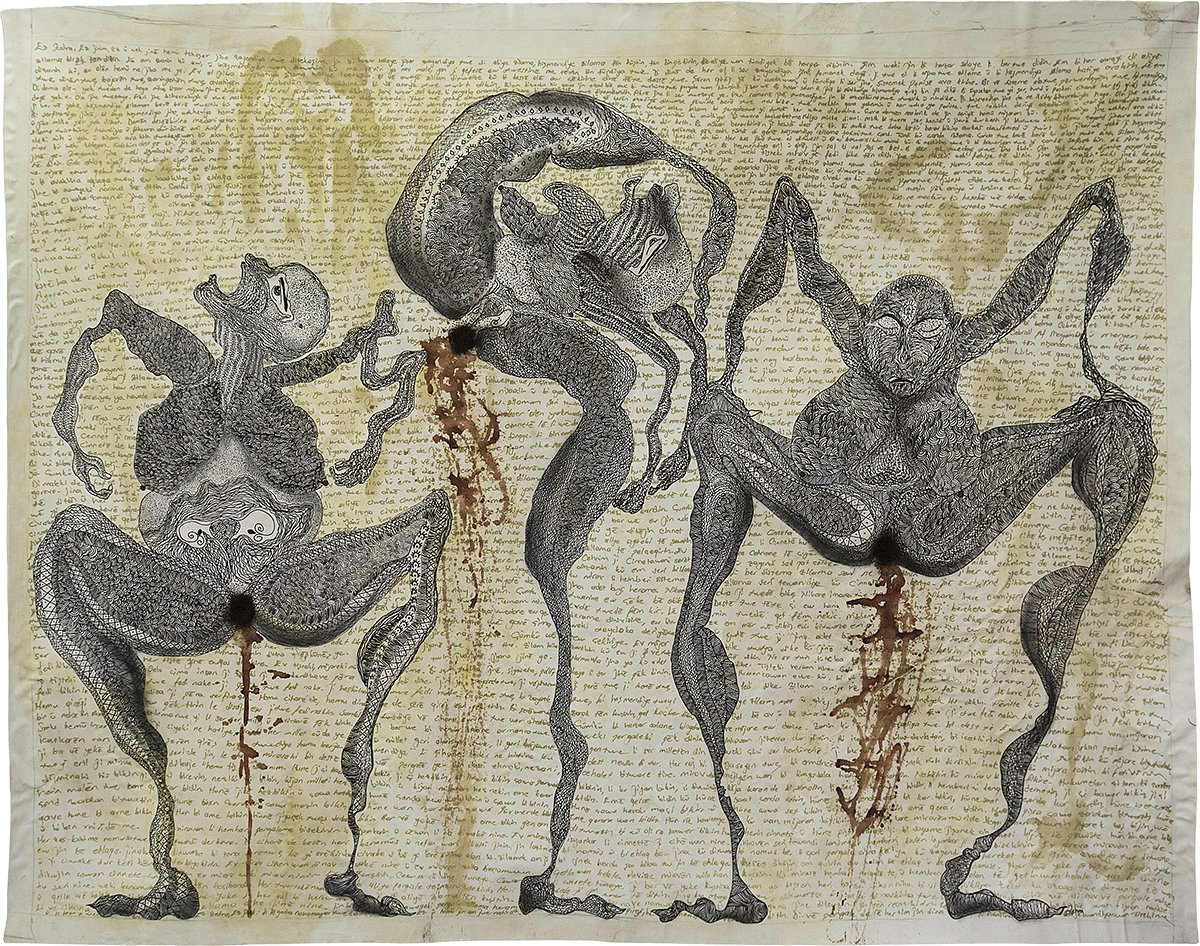

Zehra Doğan’s Haunting Visions of Incarceration

Kaya Genç’s written account of Zehra Doğan’s work highlights both its oozing corporeality, and its power to connect with bodies elsewhere and transcend the physical bounds of imprisonment within which it was created

The Militant Mother: Media, Memory, Healing

Bradford Nordeen’s invocation of Diamanda Galás’s presence brings temporary assemblies of bodies to life again

Issue 8:

PERFECTION / SPECULATION

—Genes, memes and the modifiable body

Summer 2023

Introduced by Nicholas John Jones

The mirror that shatters both image and object: social media, new technologies and the body

Issue 8 of PRAKSIS Presents brings together video interviews with four leading protagonists in the fields of new technology, identity, the body and the perception of self. Together, they provide a kaleidoscopic view of the impacts of new technologies on issues of identity and the human body. They variously reflect on the ways that algorithm-driven trends shape senses of (embodied) selfhood and desires relating to body image. Also under consideration are the ethical implications that arise when bio-technologies, perceptions and constructions of self, body modification and big data collide.

The interviews respond to the research agenda of PRAKSIS residency 18 Perfection / Speculation, led by post-disciplinary artist/designer Adam Peacock through September 2021. Residency partners The Vigeland Museum, Oslo, and queer live events coordinators Karmaklubb* contributed to its aims and activities, and the videos are conducted in the dramatic setting of the Museum’s collection of works by Norwegian sculptor Gustav Vigeland (1869-1943). Thus, each conversation focuses both on present and future perspectives—including the implications of new technologies such as social media, AI and CRISPR/Cas9 for normative and non-normative bodies—and on still-lingering concepts inherited from body cultures of the past.

Peacock’s interviewees are Natasha Vita-More, author of The Transhuman Manifesto; Mark Jarzombek, Professor of History and Theory of Architecture at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT); artist and digital culture theorist, Lev Manovich, and science-fiction artist, filmmaker, inventor and body architect, Lucy McRae. Vita-More speaks with Peacock about concepts of beauty, the role of ego and the ethics of striving to overcome ageing. Jarzombek discusses the impacts of AI and design technology on perceptions of self, while delivering some tough correctives on questions of state and corporate surveillance and the struggle of ethics to keep pace with market-driven bio-technologies and data access. Manovich reflects on issues of autonomy and originality in relation to social media and the algorithmic mining of big data, and offers important contextual reflections on the history and evolution of information technologies and cultural analytics. McRae discusses what it means to be “human” in a science- and technology-driven world, and advocates for the role of art as a catalyst for experimental, open-ended approaches to the development of knowledge in this area.

Complementing the video interviews is the PERFECTION / SPECULATION Explorer, an A1-size fold-out publication available in print and digital. One side of the Explorer provides extended interview transcripts, while the other features images of Vigeland-inspired future-body prototypes by residency artists led by Adam Peacock: Marte Aas, Jonathan Armour, Louis Alderson-Bythell, Trinley Dorje, Erika Stöckel, and Bobby Yu Shuk Pui. The artists also worked together to devise the interview questions.

Beauty, Transhumanism & The Disease of Ageing

Natasha Vita-More speaks with Adam Peacock

The Post-Ontology, Blobby Architecture & Homogenised Identities

Mark Jarzombek speaks with Adam Peacock

New Media, Instagram & Homogenisation

Lev Manovich speaks with Adam Peacock

Body Architecture, Genetic Editing & Self-Transcendence

Lucy McRae speaks with Adam Peacock

PERFECTION / SPECULATION Explorer

A print publication bringing together artistic visions for future body prototypes together with interviews with four practitioners at the forefront of body and identity technologies

Issue 7:

Tell Me Slowly Where You Stand

—Positionality, ethics, duration

Spring 2023

Guest editor Natasha Marie Llorens

This selection of interviews and excerpts reflects a growing imperative in the field of curatorial practices: the curator must ground their work in a careful examination of their own positionality. This notion of positionality should not be understood as a process of policing the authority of others to speak based on one’s own presumed authenticity, but it does imply that an individual cannot speak from “everywhere” and “nowhere”. It also insists that all makers-of-sense are bound, to some degree, by circumstances that they don’t choose. It matters who you are, even if you are never stable, never fully graspable.

Presented here in two short interviews and an excerpt from a longer essay are snapshots of three curatorial practices that I deeply admire. At a structural level, Golnar Abassi, Sadia Shirazi and Sarah Workneh integrate a perpetual question about their own positionality into their curatorial and intellectual practices. They don’t merely show us where they stand. They consistently refuse to perform a simplistic version of their identities, and their respective practices are devoted to making space and time for others to reflect on their own complex identifications. Actually, no; they don’t simply make space – they also defend that space against anti-intellectual conservatism on both the right and the left of the political spectrum, the conservatism that seeks to assign everyone a role and silence attempts to speak laterally, or to speak slowly, or to mumble.

PRAKSIS Presents’ invitation to assemble these voices in a discussion about positionality arises from an intensive month-long residency I led at PRAKSIS in 2018, “Meet me at the Empty Center.” The residency was focused on the curatorial role in social practice-based art projects. Our discussions were organized around the notion of ethics formulated in Emanuel Levinas’ work on responsibility and Jacques Derrida’s re-reading of him. In the simplest language, this view establishes ethics as a refusal of the idea that any individual person has enough perspective on a given situation to “do good”. We don’t act ethically when we behave according to a set of preset rules about right and wrong; we act ethically when we accept that many valuable things exceed our capacity to control them. However, irrespective of that lack of control, in an ethical sense we remain responsible for our actions.

I came away from the PRAKSIS residency with a new methodological language based in a deeper philosophical context, one that shows how our curatorial responsibility to one another is both inexorable and something that cannot be mastered. Having worked with Sarah Workneh and Golnar Abassi on curatorial projects in the past and spent time reflecting on Sadia Shirazi’s curatorial practice in writing, I sense that they share this understanding of what is at stake in the curatorial relation.

My time at PRAKSIS, shared with Natalie Hope O’Donnell, Nicholas John Jones and residency participants Ina Hagen, Jasmine Hinks, Maria Jonsson, Michael Mcloughlin, Rodrigo Ghattas Pérez, Maija Rudovska and Helle Siljeholm, also reminded me that the time of an ethical engagement with artistic practice is crucial. It matters who you are, but the timescale of one’s commitment to a place and set of vocabularies is just as important.

Positionality, ethics, duration: these are the concepts framing my conversations with Sarah Workneh and Golnar Abassi, and they are also fundamental to Sadia Shirazi’s text, with its entreaty to “slow down” and embrace “alternative temporalities.”

Fictioning Comfort and Other Strata of Rotterdam

Golnar Abbasi

Slo Curating

Sadia Shirazi

Into Woods: Propositions for a Third Way

Sarah Workneh

Issue 6:

Medium to Well Done

—aspects of medium and materiality

Summer 2022

Introduced by Rachel Withers

There is a distinct circularity to the idea of “medium specificity” in art. At a practical level, works of art tend to be categorised by the types of material and the material processes that they employ – if a work involves paint it is painting; if it manipulates the experience of three-dimensional space it is installation; if it proposes a particular kind of social interaction or event it’s relational, and so on. However, because art labels such as “painting”, “installation” or “relational practice” (etcetera) fundamentally rely on conventions, precedents and contingent agreements for their coherence, their parameters are constantly eroding and being reconstituted anew. The paintballing event that brings strangers together potentially redefines the manipulation of social relations as a property of painting, while the painter who transforms the floors, walls and ceiling of her gallery space has potentially recruited painting into the field of installation. And so, through their unorthodox redeployment, media and materials have the power to redefine the boundaries of art categories, while art categories have scope to reassign the significance of media and materials, in a worryingly and wonderfully vertiginous vortex.

It’s a situation that can either be pushed aside (“categories don’t matter!” or even “all this theoretical stuff is guff!”) or engaged with, enjoyed, explored or re-articulated. In 2000, Rosalind Krauss called it the “post-medium condition” and recalibrated the modernist quest for medium specificity as a grand project to define “the essence of art itself”, via works that acknowledged their specific, mediumistic historical and institutional frames of reference while testing new approaches, materials and combinations. Then, in 2003, she tightened the critical screw: “without the logic of a medium, art is in danger of descending into kitsch”! This issue of PRAKSIS Presents sagely sidesteps the first part of Krauss’s 2000 agenda (reflecting that anything and everything that calls itself “art” is in some faint sense an attempt to define “the essence of art itself”). It’s more interested in the second bit – the idea of work that deliberately reviews, recombines and reinvents its mediumistic frameworks. Drawing on its archive, it has assembled an eclectic group of PRAKSIS alumni whose works have some clear stake in ongoing questions about medium specificity, albeit in very different ways.

Robert Bordo has been making paintings for more than 50 years. In this issue he offers a detailed insight into his highly exploratory and reflective painting process, discussing how the development of a conceptual frame, the deployment of media and intense sensory attention mesh together in a complex interdependency. Anna Sofie Mathiasen uses animation and drawing to spin intricate and overlapping historical and personal narratives, but her true medium might be said to be the mask, a means she uses to reveal, disguise and complicate the artistic and social meanings of her work. Sculptor Gereon Krebber deploys many unorthodox substances as medium, and in conversation here he is invited to reflect on the subversive implications of this for established ideas of material and conceptual value. In Ina Hagen’s practice, the abstract and immaterial (language, ethics, social interactions) are “mattered”, intervened with and manipulated as media to social and aesthetic ends. Marit Silsand’s photographs ride the disciplinary boundaries of digital image-making, painting, drawing and textile art, playing games of trompe l’oeil with viewers’ expectations about the digital and the analogue – but they also spring from the subtle Proustian resonances that she finds within a humble domestic material. PRAKSIS thanks all five for their contributions and welcomes readers' responses to this issue's theme for possible inclusion on the PRAKSIS Presents site. These can be emailed to co-editor Rachel Withers via rachel@praksisoslo.org.

Painting is a little like walking the dog

Robert Bordo

Ephemeral Matters

Ina Hagen

Oh Rats!

Gereon Krebber

Introducing Zobolam, Hamlet & Cameo

Anna Sofie Mathiasen

Follow the lines

Marit Silsand

Issue 5:

Push It Real Good

—relationships between body language and social dynamics

Spring 2022

Introduced by Nicholas John Jones and Rachel Withers

Issue five of PRAKSIS Presents features artworks that explore the codes, dynamics and discourse of human non-verbal social interactions.

According to journalist Lucy Jolin, “just 7% of communication comes from the words we use” (Guardian UK, 2015). Her listicle-style piece goes on to detail physical gestures, poses and “body-language” tactics that supposedly make “the right impression on a new boss” or secure “that crucial pitch or sale”. Journalism such as this speaks to our intuition that our fellow humans notice, interpret and respond to our posture, gestures and movements; the (sometimes altruistic, sometimes self-centred) drive to decode and leverage this subtle realm of communication is strong and understandable. However, where there is strong desire, tenuous logic and debatable assertions usually also lurk. Jolin’s unsourced “7%” statistic earned waspish comments below the line from sceptics querying the idea that there’s a 93% chance of guessing what someone is saying simply by observing their body language, and among the writer’s reference texts was Amy Cuddy’s heavily criticised thesis (Presence: Bringing Your Boldest Self to Your Biggest Challenges, 2015) that striking a hands-on-hips “power pose” will increase testosterone, decrease cortisol and generally make you a more efficacious social operator.

So, evidence of the deep desires, sharp anxieties and myths that model this particular domain of power/knowledge is easy to find; questions about non-verbal communication are always of far more than academic interest. To what extent does it really influence our communications? How culturally and historically specific is it? How reliable is this or that account of it? How do we read and interpret different acts of physical self-presentation, and do our readings cohere with other people’s? The works included in this issue create metaphorical spaces to begin to review and deconstruct this freighted area of theory and practice: the desires behind it, the fundamentals and intricacies of the specific social relationships at stake in it, and the histories that inform it.

The issue’s theme was prompted by PRAKSIS residency 12: Taking Hold, The Double Bridge, an exploration of physical expressions of solidarity, competition and antagonism in social relationships. The residency was convened by Welsh artist Phoebe Davies, and it led to the production of her film The Sprawl, (2018-20), and the collectable limited edition print Flex (2018-20). Both resulted from Davies’s interactions with young female wrestlers and staff at Oslo’s Kolboltn and Lambersæter wrestling clubs. In these projects, Davies’s lens studies the club members’ physical enactment of relationships of acceptance, support, tenderness, joy, fear, aggression and transformation, within the environment of a club designed for physical training towards socially licensed combat. Female wrestling has an established history, but the sport is far from mainstream: in Davies’s work we hear one of the coaches explaining that when she first competed internationally, she and her peers wore men’s wrestling suits with t-shirts because female-specific suits didn’t exist. Davies’ moving presentation of a new generation of female wrestlers in training highlights their challenge to traditional gender norms, their parallel development of physical strength and mental resilience, and their growing confidence in their individual physical and psychological presence. Sports training emerges as an education in how to live a fuller life.

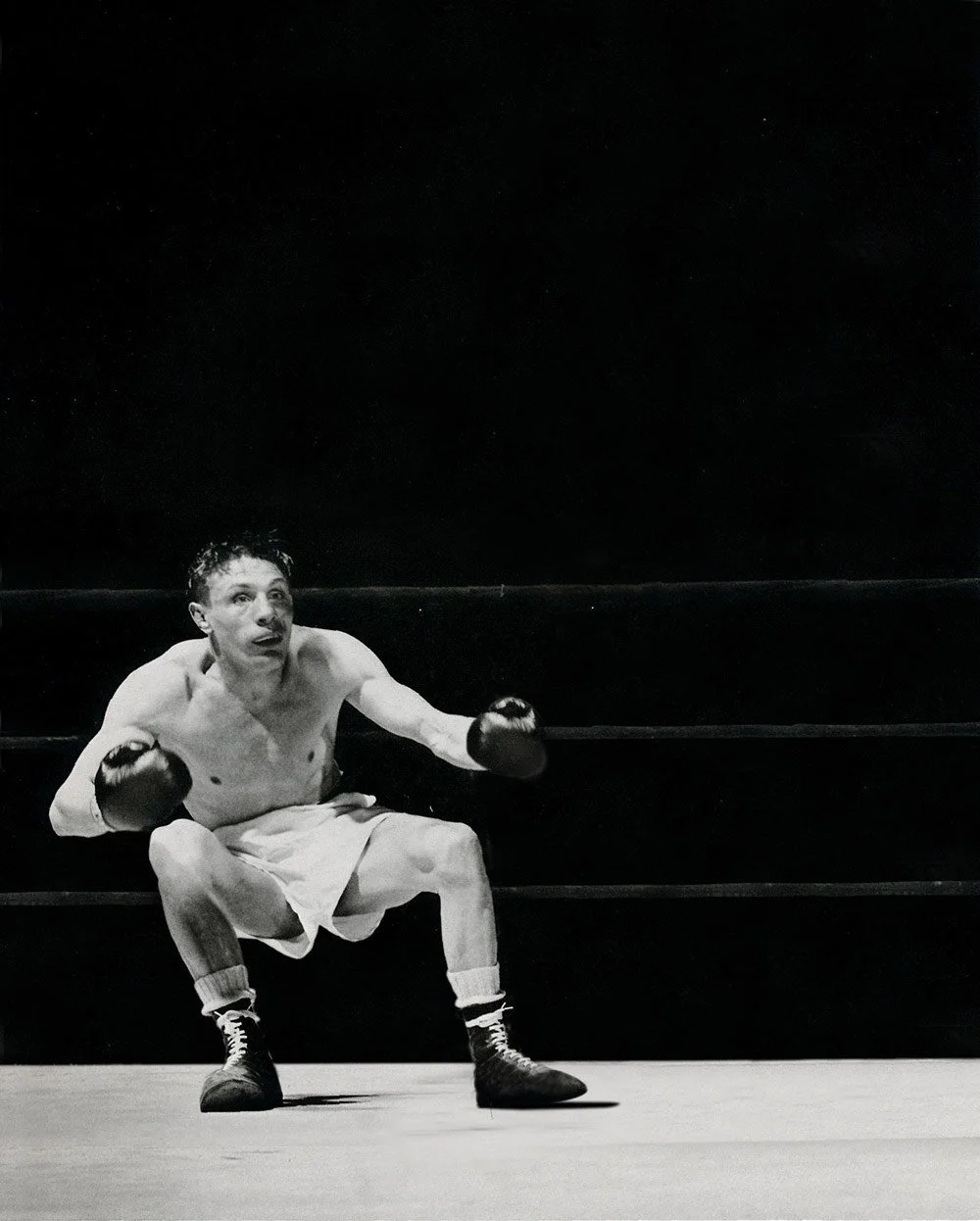

Ove Kvavik’s work Essence of the Beaten (2021) is a single image drawn from a larger series by the artist. Showing a boxer falling to the canvas, it also studies the tension, pressure and expectations that are foregrounded in contact sports. Kvavik’s image is deceptively simple, but in fact it’s a synthetic creation, an “assisted readymade” evolved by editing the winning fighter and other figures from a historic press photograph. With the competitive binary of the paired fighters and the triumphal display of the winner removed, Kvavik’s image sidelines boxing’s triumphalism, machismo and spectacular violence, making space for something very different: a poetics of loss. In his accompanying interview Kvavik suggests that loss (a central preoccupation in a number of his projects) lies at the root of poetic creation, and he proposes Orpheus’s loss of Eurydice as a mythic and metaphorical starting point of lyric poetry and ballads. The “body language” that he excavates from the photo-journalistic original reveals complex resonances way beyond the sphere of modern sport.

Silence of the Valkyries (2017) is a collaboration between interdisciplinary artist Laura Cooper and dancer Edwin Cabascango. It was developed during PRAKSIS’s mucker mate residency (May-June 2016), an exploration of the dynamics of “creating community” in the culture and environment of Oslo. A four-channel video work accompanied by a poem, Silence of the Valkyries shows Cabascango responding to the sculptures and murals of Oslo’s Rådhus (City Hall) through movement and touch. He swarms over the giant naked Valkyrie statues that stand outside the hall, testing his reach, adapting his dancer’s body to the contours of the sculpted figures and establishing an unreciprocated intimacy with their frozen bodies. Cooper’s camera approaches, retreats and moves around as it documents, becoming a third protagonist in the work’s choreography. In this dialogue of bodies enacted at the entrance to Oslo’s seat of power, the mythic, the historic and the living metaphorically intertwine and raise questions about the relationships between humanity and history. How do we register and reflect on the physical existences of the social subjects who came before us? What impact does history have on our bodies?

Roots (2020), a hypnotising song-poem by Ayesha Jordan and Justin Hicks, is usually performed live by Jordan’s persona Shasta Geaux Pop. It begins with an invocation of different physical states, an anthology of descriptors whose valences shift continuously between the desirable and enviable (“a privileged body”, “a sexy body”), the sorrowful and shocking (“a lonely body”, “a burnt body”), and the ambiguous (“a wanted body”, “a somebody”). Jordan’s richly expressive voice colours each line with subtle resonance, then intertwines with Hicks’s heartbreakingly melodic and soulful threnody (“Roots I can’t lie/Can’t lie I’m so/So low in my mind”). The piece’s wandering duet of abstracted adversity finally weaves its way towards a kind of peace and resolution. Here, the “body language” in question is not an exchange of signals between beings in physical space but a series of mental visualisations. The bodies this invokes for each listener and the relationship they have to them will be unique. However, the implications of each imagined body in relation to historical and present-day injustices and struggles towards recognition, power and agency are both unmissable and deeply moving.

Clara J:son Borg’s 28-minute film A liaison to a life no longer ordered from above (2021) invites the viewer to go on a dérive with a group of fellow creators through the dry, sunlit streets and alleys of an Athens banlieu. J:son Borg and her six companions converse with each other and to camera, physically demonstrating and reflecting on the strategies they use to “map” power in the city and manage the stresses it generates (in particular, thanks to the Covid-19 lockdown). They describe the pressures exerted by public authority and oppressive public attitudes on their own individual bodies and share their coping methods: small but significant mental and behavioural subversions that gauge their surroundings, assert their own realities, re-choreograph the city’s spaces and potentially baffle the ‘look’ of the city’s authorities. One has an imaginary companion who (somewhat like Eurydice) follows him on walks, requiring him to look back periodically and slow down so that he, she or it can catch him up. Another has invented a presiding goddess-protector who empowers her to challenge aggressors on the streets. Her explicit prototype is Lizzo, but viewers may well make another, older link to the heroes of ancient Athens and their divine allies: Athene, Aphrodite, Hera or Artemis. Acting collectively, the collaborators touch and nurture one another and relax together in the shade. They test out new words for their practices, and “percuss” a building site as if it were a musical instrument. Against the backdrop of a city that feels both abrasive and full of promise, the work trials small physical subversions that gently re-imagine physical, psychological and social relations. They combine to propose a Utopian model of the care both of the self, and the selves that surround us.

The Sprawl and Flex

Phoebe Davies

Essence of the Beaten

Ove Kvavik

A liaison to a life no longer ordered from above

Clara J:son Borg

Roots

Ayesha Jordan and Justin Hicks

Silence of the Valkaries

Laura Cooper with Edwin Cabascango

Issue 4:

It’s my house

—complexities of belonging

November 2021

Introduced by Nicholas John Jones

We all want to feel we belong somewhere, both spatially and socially; to be accepted by others is a fundamental human emotional need.

It’s my house, PRAKSIS Presents’s fourth issue, examines works that consider that desire and that need, variously probing relationships between self-understanding, people, place, behaviour and culture. Taken together, this issue’s contents consider structural obstacles to and conflicts arising from the quest to belong, as well as the ways in which people create personal spaces and/or collectivise in both physical and digital realms. The ‘house’ in this issue’s title is a metaphor for spaces where individuals or cohabitants can act and interact as they wish. However, a ‘house’ never exists outside of the social: no community can claim autonomy. It’s a permeable space, constantly negotiating exterior pressures and challenges.

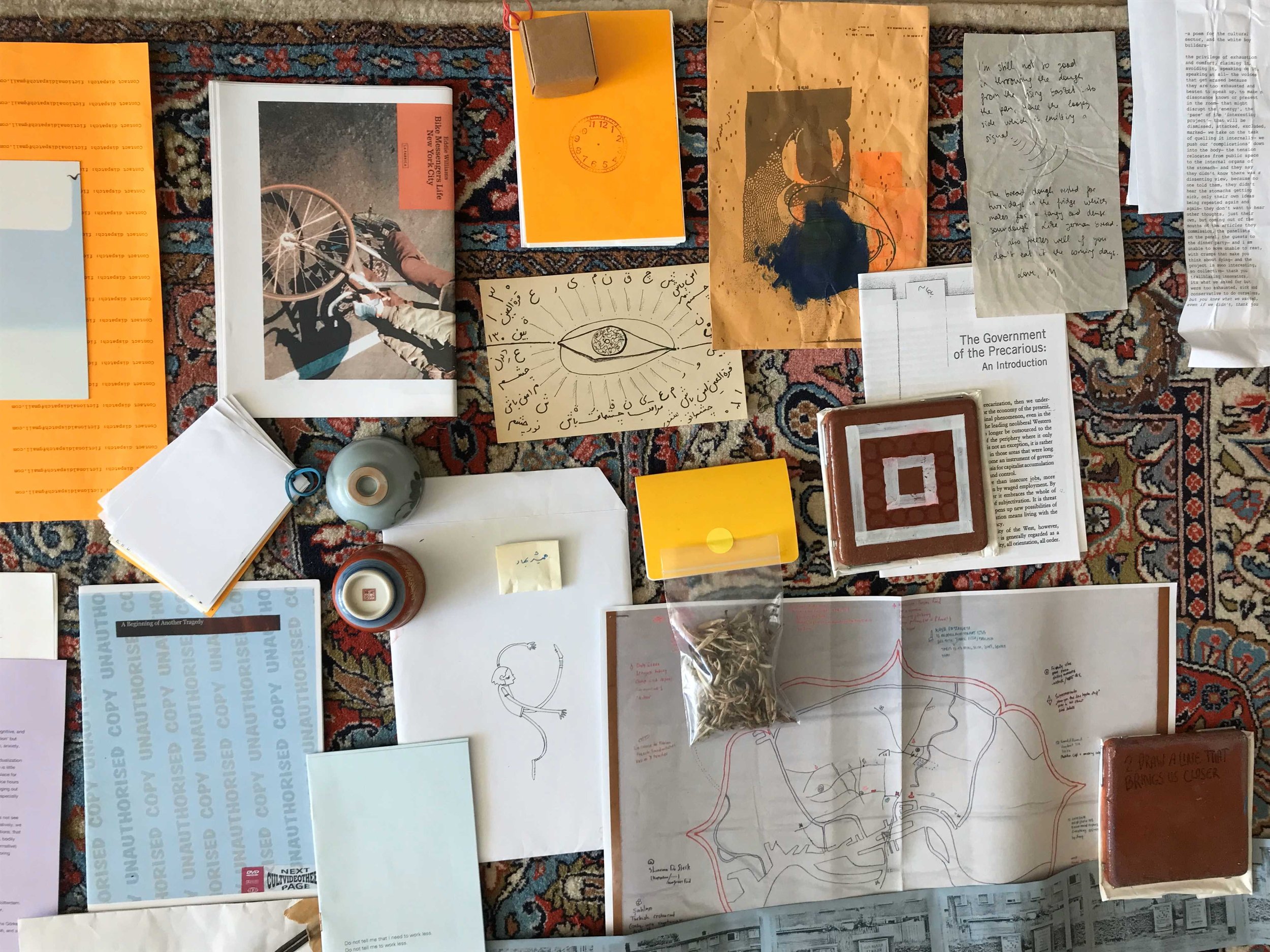

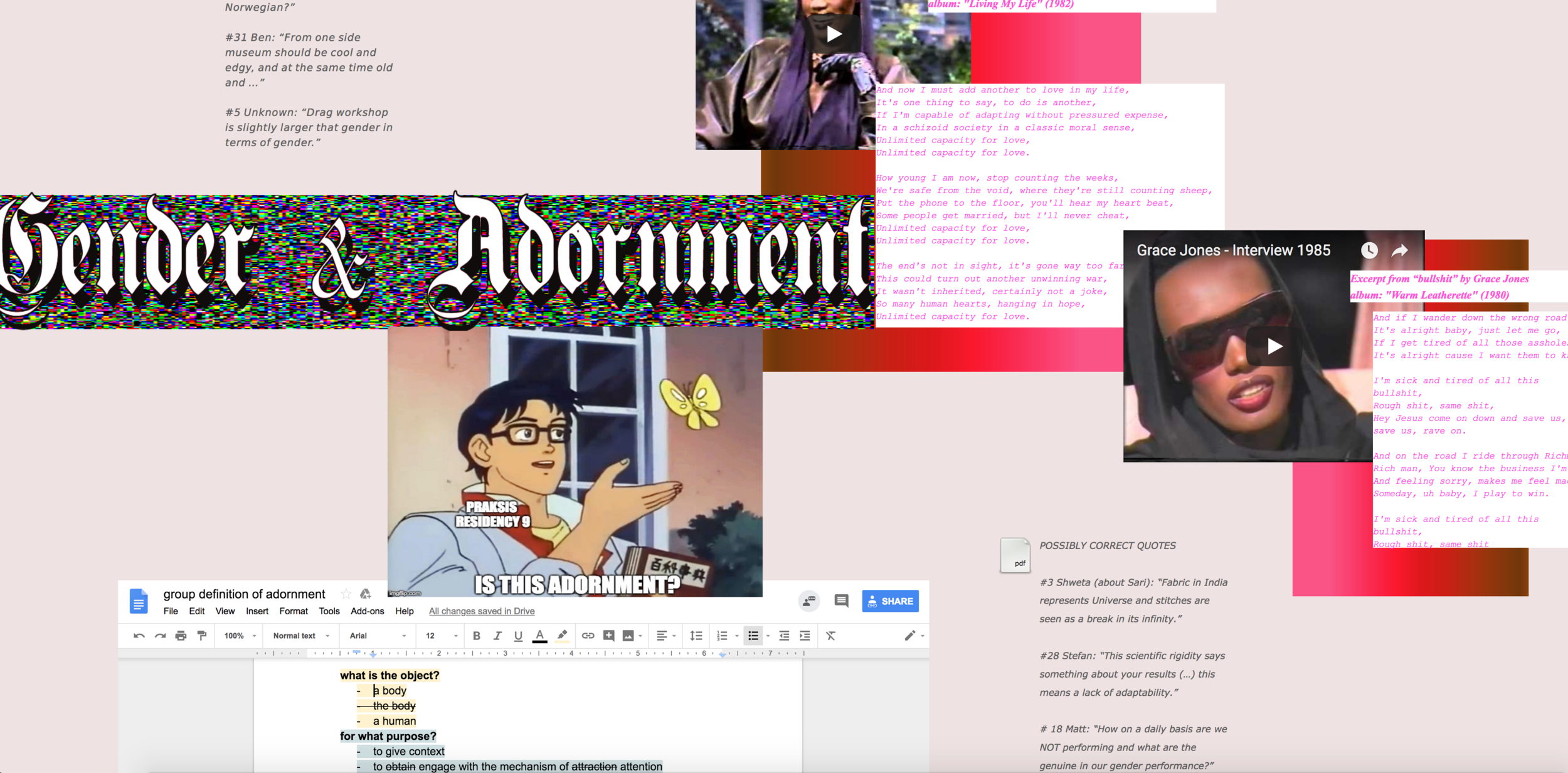

The construction of a sense of identity and belonging involves decisions about whether to conform to or reject social norms. It also requires the negotiation of what those acceptances and rejections will mean to others. Accepted social behaviours and ‘norms’ are both complex and culturally and sub-culturally specific, varying geographically and constantly shifting. Fashion – and more generally how we clothe and present our physical selves to others – is a key aspect of the formation of both collective and individual identity. PRAKSIS Residency 9, Adornment and Gender, took place in Spring 2018 and brought together a group who, spanning generations, heritages and nationalities, embodied a wide range of lived experiences. Together, they investigated the ways that identity politics intertwines with material practices of creating, putting on, customising, and mixing adornment. One outcome of their work was the Gender and Adornment website, a kaleidoscope of reflections on residency discussion points and on the key influences at play in their diverse lived and performed gender identities.

Larry Achiampong and David Blandy’s collaborative practice draws on the differences and crossovers in their family heritages and builds on the places where their artistic and critical interests coincide. Their work explores cultural hierarchies and the “fiction of the self”, looking at how history and pop culture affect the formation of individual and collective identities. Their Finding Fanon series is inspired by the lost plays of Frantz Fanon, (1925-1961) a radical humanist who dealt with the psychopathology of colonization and the social and cultural consequences of decolonisation. In his essay The Limits of the Traversable World, Steffen Krüger uses Achiampong and Blandy’s Finding Fanon II (2015) as a springboard to analyse post-internet relationships to digital spaces and post-human identities – places where human real-life and online experiences have merged, forming identities that exist outside of physical bodies and individual characteristics, possibly leaving real world differentiations behind. Finding Fanon II subverts the popular computer game Grand Theft Auto V, notorious for its popularisation of violence, sexism and racism. Achiampong and Blandy’s iteration strips its in-game environment of weapons, creating a setting in which the artists are able to explore the intersection of their biographical narratives, a process entailing struggle, the discovery of kinship and a mutual search for liberation. Krueger argues for Finding Fanon II as a demonstration that the search for post-human relationships necessarily requires an acknowledgement of origins and of the “histories of divisive, colonial practices” (Krüger, 2016). Working these through, we learn, is a crucial, mutual task.

This issue also includes a work from the Finding Fanon series –Finding Fanon: Gaiden Delete and Finding Fanon: Gaiden Delete – Sara’s Story (2016), a two-part project that draws on true stories of identity and migration, cultural history and social change. It was made through collaboration between Achiampong and Blandy and the group Mennesker i Limbo (People in Limbo) as part of PRAKSIS’s first residency, New Technology and the Post-Human. Mennesker i Limbo is a self-constructed ‘house’ for a group of people who refuse to give up on the hope of home; living long-term without documentation, they fight for recognition and strive to spread awareness of the predicament of those forced to migrate without official documentation. Like Finding Fanon II, this project also uses the virtual environment of Grand Theft Auto V, and here is serves as an arena in which to narrate the extreme, often hidden, histories of displaced people, without papers or rights, far from home. Premised on a belief in ‘belonging’ as a fundamental right for which society has responsibility, the work bears witness to the traumatic challenges facing those who, through no fault of their own, find themselves “in limbo”.

In Elenie Chung’s short film Est. Time of Arrival, (2021), a young Chinese woman is shown visiting areas of Los Angeles associated with China, while two voices – one presumably that of the film’s protagonist – engage in small talk about what we see on screen. Drawing on Chung’s own background as an immigrant to the USA (Chung is from Trinidad and Tobago and has Chinese heritage), the work reflects on the history of the interrelationships between diasporas, and how these coalesce in today’s society. Shot in an informal style using Super 8 film, the footage has a nostalgic quality that recalls home movies from a pre-digital age. The sound of a computer mouse clicking as the editor cuts between scenes disrupts this artifice and reinforces key statement in the soundtrack: “the purpose is to be fake”. We hear this as the narrators reflect on the synthetically recreated “foreign” historical spaces and landmarks that we see on screen: their claims to authenticity, and the intentions behind their construction. Throughout the film, the idea of time – and by association, progress – is used to focus on the phenomena of heritage and nostalgia. As she reflects on culture, history and personal experience Chung insinuates that the speed of time differs depending on geography, and she interweaves this perception into her subtle destabilisation of the notion of “national identity” in a globalised world.

Films from Voice is an impressive collection of short films made by a group of 15- to 19-year-olds living in the Oslo area during a film course led by artist Ane Hjort Guttu and filmmaker Brwa Vahabpour. Each of these films arose from the suggestion that personal experience can offer a good starting point for both fictional and non-fictional narrative, and invited its young participants to focus on subjects of personal importance within their lived experiences. Covering topics such as inter-generational relationships; mental health; and prejudice among others, these filmmakers bring earnest, moving concerns and perspectives that, as we consider the nature of belonging, provide insight into (and for me give heart to) a future that will become more accepting of complexities that should be appreciated as we each find our place in the world.

Finding Fanon Gaiden: Delete

Larry Achiampong and David Blandy

The Limits of the Traversable World

Steffen Krüger

Est. Time of Arrival

Elenie Chung

Films from Voice

Seven films inspired by real life

Gender & Adornment Website

Gender politics intertwine with material practices of adornment

Issue 3:

The hills are alive

—exploring sound and environment

September 2021

Introduced by Rachel Withers

Somewhere in the literature on the history of ‘disembodied voices’ and recorded sound it’s mentioned that an early rationale for the invention of sound recording was its capacity to preserve for posterity ‘the voices of great men’. This issue of PRAKSIS Presents focuses on sound, the environment, field recording and the idea of the ‘soundscape’, a concept we owe to the founder of acoustic ecology studies, R Murray Schafer. Sadly, Schafer died this year on 14th August, at the very time Nicholas and I started to edit this issue. Celebrations of Schafer’s life, ideas and works now abound online, and alongside them we find the recorded voice of Schafer himself. It is poignant to hear him speak to us now that he has gone – in particular, to hear his reflections on the precious transience and uniqueness of ‘real’ sounds (as in, unrecorded sounds: live rather than recorded speech, for example). From what I’ve heard and read, I imagine Schafer would have shrugged off the designation ‘great man’, but there is also something resonant in the thought that when we listen to his voice now, one of sound recording’s earliest motivations – to keep alive important past utterances, voiced by their original speakers, at least as an echo for future generations – is being fulfilled.

Many of Schafer’s core ideas are carried forward in this issue’s contents. Composer, sound ecologist and former colleague of Schafer’s Hildegard Westerkamp has made available to us Raven Dialogue, a seventeen-minute field recording of the winter soundscape of Saltspring Island, approximately 40 kilometres south-west of Vancouver, and she accompanies this with a short contextualising text. The recording initially seems sparse and austere but (in Schafer’s words) by ‘using our senses properly’ and listening with full engagement, we find ourselves immersed in an acoustic environment that is both saturated with subtle detail and spatially expansive: ‘mapped’ by a 360-degree long-distance ‘conversation’ between ravens in which the hiatuses seem as significant as the birds’ cries. ‘The existing soundscape is made of energy,’ Westerkamp notes, in her talk in this issue. ‘When we listen with intention, we meet that energy with our own,’ and we start to make discoveries. In Raven Dialogue, for example, we find that sound can have a temperature. With its continuous, complex crackle of melting ice and an occasional crunch of snow underfoot, this is the very sound of icy cold. ‘When you listen carefully to the soundscape, it becomes quite miraculous,’ said Schafer, but he also pointed out it is a practice that takes work and reflection. All of the works in this issue are born from processes of sustained and intensely close perception. They offer a great basis for deep listening and, we also hope, for ‘understanding yourself as a listener better,’ to borrow Westerkamp’s phrase.

Schafer observed that real, individual sounds are absolutely unique and unrepeatable. In the past, before the invention of sound recording, ‘every sound committed suicide, you might say, and would never be heard again – not exactly the same way’. The contributions we’ve included by composer and sound artist Annea Lockwood and sound artist and founder of the Gruenrecorder label Lasse-Marc Riek both chime with this idea. ‘Experience doing field recording clearly shows you that sound is unpredictable and can’t be controlled. The accidents that arise demonstrate the infinite number of variables in play’ notes Riek, while Lockwood underlines the centrality of sound’s unpredictability to her own practice as a composer, performer and field recordist. ‘If I like a particular mix of sounds at a certain spot on a river, I need to record it right away; tomorrow, that water riffle will be different, or might have vanished altogether,’ she observes.

Those who record the planet’s soundscapes do so with a deep concern not just for the uniqueness of original sounds, but for the creatures and conditions that create them: they too are under threat of disappearance and this knowledge is central to many of this issue’s discussions. The four recordings by Riek included here are extracted from Helgoland, a larger work sound-mapping the Heligoland archipelago – a wild and biodiverse environment that, thanks both to sheer chance and some recent human interventions, has survived earlier attempts at its annihilation. Riek characterises the work as a literal and metaphorical study in ecological resurgence – of the drive to survive. We experience this drive powerfully, indeed viscerally, when we listen to his recording of guillemots diving from the Heligoland cliffs into the sea. Yes, this is a recording, but when we give ourselves fully to the sound it becomes an electrifying, almost shredding, aural encounter with raw life.

Annea Lockwood’s Wild Energy also immerses the listener in the sounds of powerful elemental forces, but what we hear in the extract she’s provided introduces us to a different order of listening: something we might describe, borrowing a phrase from Walter Benjamin, as the aural unconscious. Benjamin’s ‘optical unconscious’ identified the new, paradoxical realm of unseeable things rendered visible to the human eye by photographic technology. Wild Energy is built (at least in part) from sounds that shape our world but that are inaudible except via technological intervention: for instance, the splitting of trees’ internal water columns at a time of drought, or pressure waves travelling under the surface of the sun, or the ultrasonic cries of bats and the vocalisations of Sei whales. Wild Energy can be experienced fully in a rural outdoor location at the Caramoor Center in New York State, and it was created to be heard within that wider soundscape; it is about connection. Lockwood’s purpose is not to amaze her listener with other-worldly sublimities but to cement our sense of our ‘visceral connection to earth’s forces’. She does this by introducing us to a soundscape that is both extraordinary and a constant underlying, unconscious component of our earthly lives.

Tze Yeung Ho’s essay is importantly a manifesto plea for biodiversity at the level of speech and song. In it, the composer explores the classical music world’s fixation on a mythical ideal of ‘pure’ performance: the reproduction in sung performances of ‘authentic,’ ‘perfectly accented’ articulations of different languages. ‘Accents are an essential part of us as human beings’, he points out. Rather than fetishizing an impossible ideal of perfection, he asks, why not re-focus on the affective and musical qualities of performance and celebrate the constantly-evolving ‘heard identities’ of individual performers? For Ho, individual, local and regional vocal identities are not an obstacle to be eliminated but a rich resource for a composer to be explored and inspired by. In his essay, he shares the approaches and tactics that he uses to put this ethos into practice.

This issue’s theme arose from PRAKSIS’s Residency 17, Climata: Capturing Change at a Time of Ecological Crisis. The scheduled start of this residency in Spring 2020 coincided with the outbreak of Covid-19, but its participants responded resourcefully to the changed formats that lockdown compelled. Working collectively and communicating online, they produced two radio broadcasts that documented their acoustic explorations of the places in which they were sheltering, and thus these two programmes present a montage of intimate “lockdown soundscapes” from three different continents. Alongside the Climata broadcasts are a series of talks that were further rich components of the residency’s programme of learning, discussion and development.

Seamus Harahan wields his video camera in a way that bears many comparisons with the acoustic field recording tactics of our other contributors. He videos the ‘found activity’ that he encounters while roaming in (usually) urban locations, and this forms the starting points for his finished works. In Crow Jane, Harahan’s camera homes in on a crow that has taken fervent possession of a straggly scrap of unidentifiable, presumably edible, stuff. He studies the bird as it defends its prize against all other avian comers. In the process, the scrap disintegrates and the crow’s treasure becomes smaller and smaller; at one point, the bird tries to gather all the fragments up in its beak, but fails. Crow Jane’s soundtrack, a grimly melancholy song by Skip James in which the narrator laments shooting down the woman he loves, forms a pregnant parallel to the bird’s behaviour and signals to us that it is human perversity, not bird logic, that is under Harahan’s magnifying glass. It’s tempting to scale this parable up to global scale and think about the ways that human beings’ extractive activities are dissipating the basic resources we need to stay alive and destroying both landscapes and soundscapes. “You know I never missed my water till my well went dry…” We say thanks to Seamus for letting us use this work as a kind of ironic coda to The hills are alive – and to all our contributors, for their generous and active collaboration in the realisation of this issue of PRAKSIS Presents.

Helgoland

Lasse-Marc Riek

Crow Jane [for Nora Joung]

Seamus Harahan

Working with (not against) heard identities in music

Tze Yeung Ho

Wild Energy

Annea Lockwood

Raven Dialogue

Hildegard Westerkamp

Tuning in, Sounding out

Talks and radio sessions from residency 17, Climata

Issue 2:

Heavy burdens, Happy burdens

—probing complexities of making art work that bears witness to processes of history

Summer 2021

Introduced by Rachel Withers

The sky is blue, the path is dusty and dry, and the artist is striding along with his wooden staff in hand and his easel slung on his back. Seeking the warmth of the morning sun on his face, he has swept off his hat as he goes. It is swinging in his other hand as he nears his two acquaintances, who’ve been waiting for him at the bend in the road. They make a considerable show of doffing their hats in greeting. “Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet,” says the younger-looking of the two, who is conspicuously smarter and more self-possessed than his companion. “You have every indication of excellent weather for your day’s work.”

Gustave Courbet’s reply is unrecorded and indeed totally hypothetical, since the encounter represented in his famous 1853 painting The Meeting is a “real allegory” and a complex fiction. (It is also a “speechless” one, in the sense that all its personnel are shown with their mouths shut; maybe it’s this that tempts one to add one’s own dialogue). It is a work that makes various powerful truth claims through its reflexive use of allegory: for example, by positioning the artist himself within the picture’s frame, as a witness, a truth-teller and the bearer of a historical as well as a literal burden. Back in the 1960s art historian Linda Nochlin established that Courbet’s self-portrait in The Meeting reiterates nearly millennium-old iconography: he painted himself as the mythical figure of the Wandering Jew. Having sinned in some way against the living Christ, the Wandering Jew was doomed to roam the earth until the Second Coming: he is the embodiment of endless witnessing, a kind of “walking proof”. The Wandering Jew’s identity and narrative have been reinvented and reinvested ad infinitum, and for the radicals of the nineteenth century he symbolised the oppressed manual labourer, a kind of worker that Courbet manifestly was not. That complicates but does not necessarily undermine the manifesto call for freedom, independence and dignity in labour painted by Courbet into The Meeting. The man greeting the artist is his patron Alfred Bruyas, the affluent bougeois who commissioned the picture in which he appears. Courbet shoulders his backpack with conspicuous ease and responds to Bruyas, in beard-language, that the old patron-client relationship no longer applies.

Jane Blocker concludes her 2009 book Seeing Witness: Visuality and the Ethics of Testimony with the proposition that under certain circumstances, “contemporary art can productively throw into question the claims that are made on the real and at the same time maintain an ethical responsibility to reality” (p. 128); it can also help us to see, appreciate and interrogate the subject or the apparatus that sees. Courbet’s paradoxical realist allegory shows that older practices have achieved this too, and its interweaving of ancient imagery with the figure of the artist as witness and the bearer of a burden of responsibility makes it, I think, a pregnant companion and introduction to the diverse works we’ve brought together in this issue of PRAKSIS Presents.

Heavy burdens, Happy burdens probes the complexities, responsibilities and possibilities of making art works that bear witness to processes of history or memory. All the featured works use historical materials, mythological imagery or traditional narrative to address present-day issues that are both personal and global in their importance. In the process, tricky questions relating to reality, truth, identity, subjectivity and seriousness are thrown up. Each work has its own particular reflexive relationship to its historical subject, and in different ways they all ask their audience to reflect on this. In some works, the artist’s affective labour is a conscious point of focus: bearing witness can be heavy but it can also be joyful, sometimes at one and the same time. In others, distancing strategies are explored: for example, by hypothesising the potential of decentering the anthropocentric view within the representation of ecological crisis. And while reflecting on this labour and these approaches, viewers are prompted to think about their own responsibilities as fellow bearers of the burdens of history and memory.

A statement by PRAKSIS 2019 resident Syowia Kyambi was key in helping us crystallise this issue’s theme. “We carry our histories on our backs, hunched over and barely heard, constantly swimming against the stream… The body holds, codes and re-codes, sharing a multitude of layered stories… Collective history weaves a web in the memory of our contemporary bodies.” In her video essay Becoming Kaspale, the artist reflects on the emergence of Kaspale, a multifaceted, creolised avatar or performance medium through which Kyambi revisits and processes the trauma of living through Kenyan dictator Daniel arap Moi’s regime. Kaspale is a “joker”, but a very serious one; their mission is the symbolic demolition of Nyayo House, a physical embodiment of, and metaphor for, Moi’s nationalist-authoritarian ideology. As we listen to the artist’s voice, we watch her on screen; ochre, silver and gold help prepare her body for the transformation. It’s been exciting working with Kyambi on the resolution of Becoming Kaspale, and we thank her – and indeed all our contributors – for their active participation in the PRAKSIS Presents editorial process.

Sayed Sattar Hasan’s Portrett av Hasansen also focuses on self-reinvention as a means of interrogating notions of personal and collective heritage, and the spirit of the joker is also alive in his work. Portrett av Hasansen marries a photographic portrait of Hasan with an iconic 1896 image of the Norwegian explorer and polymath Fridtjov Nansen. This gives birth to “Hasansen”, a charismatic masquerader who seems to partake of the unorthodoxy and daring of both his (male) parents. Hei, Herr Hasansen! Like Courbet, the figure of Hasansen announces a certain disregard for proprieties and hierarchies, but when we look at this work it is not possible to forget the wider historic and social legacies, preconceptions and prejudices against which Hasan pitches his photographic-performative gambit.

Nina Torp’s Methods of Pattern Making [Lepenski Vir] is a work in progress – a drafted first chapter of a video project that will probe the intellectual and ideological frameworks within which some of the world’s oldest archaeological remains were rediscovered and that continue to shape their contemporary display. As in an archaeological dig, Methods of Pattern Making is stratigraphic. It overlays and filters visual documentation of ancient remains with patterns and forms that meld modern rationalist schemata and modernist aesthetics. However, the goals of Torp’s personal stratigraphy are poetic and critical rather than rationalistic, and designed to activate the viewer’s own questions about the present-day interests and needs that inform contemporary presentations of the deep past.

Juan Covelli’s El Salto is also a first instalment of a larger project that he hopes to complete in 2023. It focuses on El Salto, a famous “natural spectacle” to the south-west of Bogotá, and reflects the artist’s concerns with digital colonialism and its impacts on people and the environment, alongside his practices of detailed research into the histories of representation. This multilayered work posits “landscape” not simply as an artistic genre but as a technology of colonial domination, and its response to this is to propose a delegation of the “burden” of representation to non-human agencies. By opening ourselves up to the point of view of machines (algorithms, drones) and subordinating the idea of human agency, it asks, might our species discover better ways of deploying the powerful technologies we have developed, and learning to live within rather than to “master” the global ecology we are presently destroying?

Eliza Naranjo Morse’s Light from Love is a gesture of giving. It consists of a downloadable PDF that can be printed as an unlimited multiple work: a small card bearing an image and a poem, that can be gifted without limit. Optimistic and full of compassion, it shows a collective of animals, each carrying a small cargo or backpack, against a background that reminds us of the wider cosmos we all inhabit. Naranjo Morse sees this work as representative of a worldview that she has been fortunate to inherit from her elders, and hopes that it will evoke reflection and consideration of how the choices we make affect others, now and in the future. We might read Light from Love as a token of the kind of selfhood - one that accepts its instabilities, dependencies and vulnerabilities, and that learns to carry its hard inheritances, if not joyfully, then willingly - that many now advocate as the only solution to contemporary society’s problems.

El Salto

Juan Covelli

Portrett av Hasansen

Sayed Sattar Hasan

Becoming Kaspale

Syowia Kyambi

Light from Love

Eliza Naranjo Morse

Issue 1:

I give to you & you give to me

June 2021

—looking at processes of giving and exchange in the arts

Introduced by Rachel Withers

During the PRAKSIS team’s early planning meetings, a conversation arose as to whether the “Presents” in “PRAKSIS Presents” is acting as a verb (“PRAKSIS is pleased to present…) or a noun (“here, in this part of our website, are presents from PRAKSIS”). It’s doing both, of course. PRAKSIS Presents is an anthology of diverse, interesting and stimulating presents for the eye and mind, presented month by month during the organisation’s fifth birthday year and planned to continue beyond it: a way of sharing PRAKSIS’s ongoing activities, conversations, projects and exchanges, as well as highlighting items from its increasingly well-stocked archive, to as wide a public as possible.

To underline the double meaning, we have tied up this first instalment with a big bow, sparkly paper and a gift tag saying “I give to you and you give to me”. This is the opening line of True Love, a Bing Crosby and Grace Kelly duet from the 1956 musical High Society, and so PRAKSIS Presents’s very first gift to you is an earworm, and maybe a rather undesirable one at that. (For the recor, it’s said that the only way to get rid of one earworm is to trade it in for another. My recommendation would be Stevie Wonder’s “Yester-Me, Yester-You, Yesterday”, overheard, yes, yesterday at the supermarket. That will potentially stay with you for days.) Maudlin and hollow-sounding, True Love would be an ideal candidate for redeployment in a Scorsese-style film edit: extreme violence on screen, Bing and Grace simultaneously schmaltzing away over the Dolby stereo speaker system.

Sorry for the unpleasant image, but that’s the way present-giving goes. Gifts are complicated things whose very definition is up for grabs, and the nature and value of gifting systems are (and have long been) open to debate. The exchanging of gifts may constitute the most basic expression of the human social contract; it can be a way of saying “I recognise your humanity; let’s work together”. It can be a means to gain practical and symbolic leverage, as in the famous truism about the non-existent “free lunch”: to give a gift is to create an obligation and to receive one is to become indebted. Gift-giving can be a threat or sneak attack (as in the offer you can’t refuse, or those pesky ancient Greeks bearing gifts) but it can also be an act of wild, reckless extravagance, an acte gratuit and an end in itself. Gifting systems can be an assertion of a specific kind of cultural identity and status, or a gesture of resistance in the face of other economies (neoliberal capitalism, most obviously). The gift can also be a medium, a platform for creative expression. Within capitalism, artists are persistently implicitly or explicitly characterised as spontaneous, selfless, unstoppable givers of social gifts. The triangular relationship between gift economics, market economics and the practice of making art keeps recurring as both a problem and a field of possibility in theories and discussions of contemporary art and culture.

Within this issue, 2017 PRAKSIS resident Famous New Media Artist Jeremy Bailey introduces YOUar, an experiment in the creation, curating and marketing of Augmented Reality art that speaks directly to the complexities mapped out above. YOUar is an online gallery that shows and distributes AR sculptures – a fun way, as Bailey explains, to collect significant three-dimensional pieces without the housekeeping hassles presented by great big lumps of physical stuff. However, there are twists in Bailey’s business model. For example, all YOUar’s sculptures feature the artist as well as their work. In his own piece Brass and Wood Semicircles (2020), Bailey appears in his hallmark awful white polo and sawn-off jeans, cheerfully (and ridiculously) hefting the monumental work of the title, Atlas-style, into the air.

There is no need to beware these artists bearing sculptures, though, because YOUar’s go-getting marketing rhetoric is a little deceptive. In this gallery, 100% of each work’s selling price goes back to its creator, and most of the artists represented are female and/or of colour: in other words, not part of the big-bucks artworld’s continuing dominant demographic. So, for both Bailey and YOUar’s collectors, the trading of artwork evidently has a good deal to do with the assertion of a social contract that rejects standard capitalist economics and ensures that artists’ social gifts should not be acquired on the cheap. Bailey reports that many customers choose to pay more than the asking price for the works they collect. Arguably, among the key gifts being traded via YOUar’s at times laugh-out-loud virtual sculptures are the senses of resistance and solidarity, and a positive rejection of the capitalist “art of the deal”. For PRAKSIS Presents, Bailey has worked with Chicagoan artist and feminist Shawné Michaelain Holloway to produce a special edition of her work “emphasis on the Y (or the first time I gave my girlfriend head was in Indiana).obj” (2021), in what he describes as “a lesbian-forward colour palette of delicate lavender”. Within this issue’s pages you will find Shawné and her Robert-Indiana-inspired work, and can saucily twirl them both through a full three hundred and sixty degrees before you buy. We challenge you to resist investing!

In her trenchant and detailed essay Access to Tools, U.S. West Coast artist and musician Nina Sarnelle sets out some historical, economic and ideological contexts for understanding The Whole Sell, a barter-based e-store which she co-created following her involvement with the 2020 PRAKSIS residency Live or Buy. By browsing each work listed in The Whole Sell, viewers will discover the barter “price” its creator has set for it. Works can be swapped for uploads of specific photos or video footage, donation to chosen campaigns, or other tasks (“touching a Tesla”, the creepy task – or dare – set by artist Chester Vincent Toye, being one of the most peculiar).

Sarnelle locates the inspiration for the project in Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog (1968-71), and specifically in its ideological problems. Her essay indicts the Catalog’s galloping individualism and white, male ethnocentrism and traces the evolution of these tendencies into high-tech neoliberalism. “The WEC,” she writes, “peddled a quasi-libertarian ethos based on a naive blend of DIY meritocracy and tech optimism: the same ethos that inspired the founding fathers of Silicon Valley.” The ideological “tools” of Brand’s Catalog, she points out, have in the long term brought us globally distributed “surveillance, mass data collection and algorithmic oppression”; commodification and gamified lives, heightened alienation and a deep social polarisation fostered by digital and social media. Sarnelle goes on to discuss the significance of The Whole Sell’s substitution of a visualisation of a black hole for the “Blue Marble” view of the earth featured on Brand’s Catalog cover. An anti-triumphalist, “terrifying image” pointing up the fragility of human existence in a basically indifferent universe, the “donut” of the black hole is designed to counter the narcissistic geocentrism of the earlier publication’s imagery.

The Whole Sell, Sarnelle explains, attempts to think through the complexities of critical cultural production in conditions where art production seems deeply implicated in capitalist patterns of exploitative labour, and where there is clearly no “outside” from which to launch a critique. Drawing on the ideas of (amongst others) Andrea Fraser and Audre Lord, she frames The Whole Sell as a way of posing immanent critical questions (“What is cultural capital? How and why do artists sell ideas? What’s the difference between interaction and transaction?”) and proposing “modest”, “tentative” and “ephemeral” alternatives to business as usual. “Each piece [on the site],” she suggests, “becomes a small gift to be “repaid” in reciprocal acts, initiating a reflection on what we each value in art, culture and relationships… The Whole Sell has been engineered as a kind of tool, providing an alternative framework for art distribution, valuation, exchange and interaction.”

The interrelation of gifting, gift economics and art making forms one important facet of this issue’s theme. Equally important are the practices of creative hybridisation, cross-fertilisation and “infection”, in positive (and also maybe not so positive) senses. Since the start of 2020, responsible people around the world have been striving not to give to each other: muffling our faces, washing our hands, coughing into our elbows and avoiding one another entirely in an effort not to pass on a potentially deadly disease. The soundtrack for this would be “I’ll try my best not to give to you, and thank you for not giving to me”. Nevertheless, at PRAKSIS as elsewhere in the art world, the drive to give and receive imaginative gifts, to infect others’ imaginations, to feed one’s own work and ideas through a collective process, would simply not be stopped, and throughout 2020 up to the present it has continued and flourished online.

The residents of Climata: Capturing Change at a Time of Ecological Crisis, scheduled to run in Oslo in the spring and autumn of 2020, were particularly hard-hit and particularly resilient in their response. Meeting digitally to pursue questions of sound and ecological change, the group recorded and shared the aural environments in which they were immersed during the unexpected condition of a pandemic lockdown. One upshot of the residents’ interactions is Climata: a hub for sound and ecology, launching imminently and to appear soon in this issue. The project is intended as a global repository for field recordings that reflect and investigate changes in the world’s aural environment: reflections of a time of crisis, but also potentially motivations for change and inspirations for practical kinds of remedial action. While unwanted sound constitutes noise, wanted sounds might be thought of in a Cagean sense as sharing the condition of music, and the possibilities that digital technology offers to share the ephemeral phenomenon of sound across time and continents seems deeply poetically – and also politically – resonant. The hub’s content will be freely available online and contributions responding to its various sub-sections are actively sought; please consider getting involved.

The politics and poetics of collaboration were also of crucial concern to the participants of PRAKSIS Residency 7, For a Rainy Day: Publishing as a Site of Collectivisation in autumn of 2017. Slowly evolving section by section following this residency was the print publication Don’t Rest, Narrate, produced by Oslo’s Torpedo Press and designers Eller med a and launched via an online event in Spring 2021. Partly a collectively designed artists’ book and partly a reader, Don’t Rest, Narrate contains sections looking at radical publishing and the art of the book, the politics of collaboration, copyright and copyleft, and more besides. One of this project’s priorities was to try, through the strategic, collectively-conceived combinations of image and text that punctuate the book, to embody the affects of a shared creative process, with its tensions, misunderstandings and miscommunications, surprises, hilarity and joyful epiphanies. This issue of PRAKSIS Presents includes links to a video generated collectively by the residency group, plus the recording of the book’s launch discussion. Copies of the book are available and purchasable via PRAKSIS’s website.

This issue also features a conversation between Nicole Rafiki, creator of the Norwegian cultural project RAI (Rafiki Arts Initiatives), and PRAKSIS director Nicholas John Jones. RAI was founded to provide a platform and meeting space for Black Norwegian creatives, and it is presently at work developing art-therapeutic community projects for the Oslo area and working with OCA (Office for Contemporary Art Norway) to showcase work by artists whose approach is, in Rafiki’s words, “transnational and complex”. RAI’s agendas are inflected by ideas of fluidity and liminality — identity and culture understood as multi-centred, mutable and heterogenous. In her interview, Rafiki reflects on her early experience growing up in a largely white Norwegian monoculture: a key influence in her project to create environments “where race is not a defining factor.” Jones and Rafiki will be in frequent dialogue as she expands and develops RAI’s projects and networks - a trading of ideas that will undoubtedly be of great mutual benefit to both organizations.

Last but not least in this issue’s collection is A Tapeworm without a gut (sketches for disaster protofiction), a digital project combining still and moving image and text by artist and writer Gary Zhexi Zhang, a participant in PRAKSIS’s first (spring 2016) residency, New Technology and the Post-Human. Zhang’s Tapeworm takes this issue’s theme of exchange in a different, maybe disquieting direction. His interest is in the fascinating dynamics of parasitism, a situation where an invading organism helps itself, unbidden, to the hospitality of a host body but in the process (needing to keep its host alive) effectively and paradoxically becomes a kind of host itself. One of Zhang’s inspirations was the parasite louse Cymothoa exigua, which, he writes, “takes the place of the tongue of a fish — squats firm on the tongue of the host — shuffles in between the cheeks, and makes itself at home... The bug sucks, supplants, and inhabits, introducing itself to the mouth in place of the native tongue which it has secretly drained of blood. The fish is left largely unharmed, somewhat augmented. The louse is a homemaker; the uninvited guest becomes the unexpected host.” Parasitism is undeniably a kind of giving and receiving – but a very, very posthuman kind, devoid of any hint of the operation of a social contract. “The parasitical invitation refuses exchange value, rejecting the commensuration of a transactional ethics,” Zhang observes. In the course of this introduction I have travelled from earworms to tapeworms, and maybe I’ve now gone far enough; sorry, again, for starting this text with one unsavoury image and ending with another. I’ll get my coat, as the saying goes, and leave you to explore PRAKSIS Presents’s first issue at your leisure. We hope you enjoy our present!

YOUar

Jeremy Bailey and SHAWNÉ MICHAELAIN HOLLOWAY

Access to tools

Nina Sarnelle

Don’t rest, narrate

On art, publishing & collaboration

A tapeworm without a gut (sketches for disaster proto-fiction)

Gary Zhexi Zhang

You are safe here

Nicole Rafiki and Nicholas J. Jones discuss motivations and approaches for creating community

Climata - A hub for sound and ecology

Experiments and resources (image - Elly S. Vadseth)